In the late 80s and early 90s, the Taiwanese, with their huge capitals, decided to sweep all the old pu-erh tea cakes off the market before the craze started. Subsequently by releasing books, writing websites, magazines, demand was created, with the taiwanese beaming because they now have a huge supply. But what was pu-erh tea before the Hongkong people started drinking them? What was pu-erh tea before the influence of the Taiwanese, or before the creation of the cooked method of production?

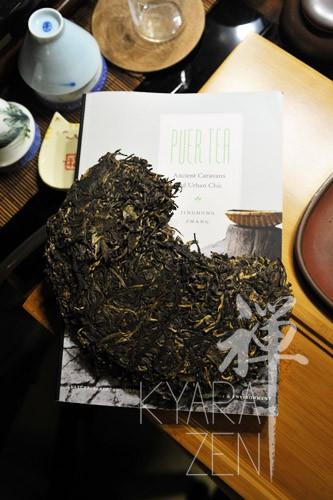

This lovely book, Pu-er Tea, Ancient Caravans and the urban chic, is an excellent anthropological study into pu-erh tea. The author, Yunnanese herself, was able to penetrate deep into the pu-er production areas, and through her neutral interactions with plantation owners, people of the tribes, tea traders, merchants, factories owners etc, she was able to present a clear, and precious account on Pu-er tea, all the way to the origin. Here’s my copy, which i enjoy together with some good yiwu mahei, a marriage of yiwu tea stories and delicious yiwu tea.

Published together with the book are lovely, unedited videos that gave readers insight into the happenings on the ground which you can view here : http://www.washington.edu/uwpress/books/Zhang_PUER_TEA_videos.html

The storage of pu-erh tea has been heavily under debate and crossfire for a long time, both on english forums and even more in the chinese ones. Those that favoured the Hongkong style of storage, which gave a reddish brown liquor, mellow, often with a warehouse scent i.e. that of old books, musty storage spaces etc, would think that the HK storage is the best, devising strategies to have teas stored in humid southeast asia for a few years before returning to HK for HK treatment. But is that the original and the only way? Some people think so, but in Yunnan, it is not the way they drink nor store pu-erh.

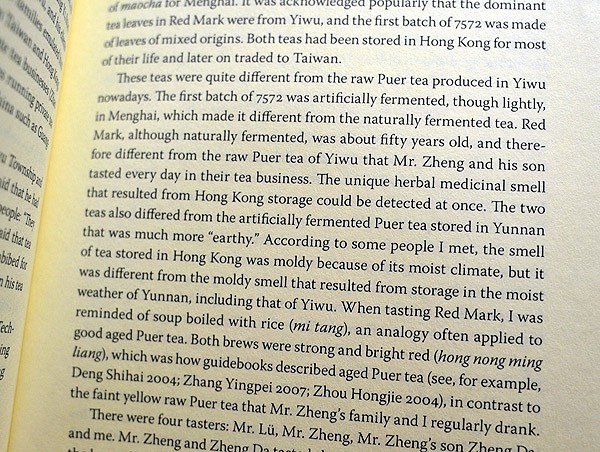

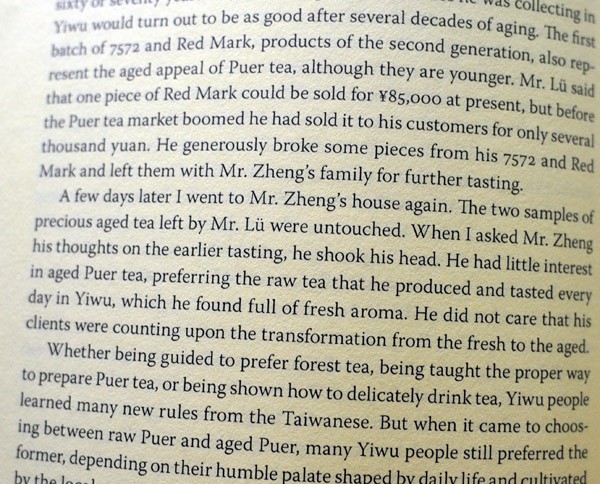

In Yunnan, amongst the tribes, pu-erh tea was formerly a beverage that involved them cooking the tea leaves into a soup using bamboo containers (served in a bamboo cup or tube). Yunnanese people also traditionally drank pu-erh tea as a “green” tea, and never oxidizing/storing them in warehouses till they become “semi-fermented”, neither did they drink pu-erh that was treated with “wo-dui” processes, i.e. soaking in water, kept damp, warm, covered with blue tarpaulin for weeks etc to encourage microbial activity. You can read an excerpt here, where Mr Zheng, of Zheng Si Long factory in Yiwu, famous for high quality yiwu teas in the early 2000s, had absolutely no interest in the hongkong style stored products, not even the famous “tens of thousand dollars” red mark. If you watch the videos, there is also one thing that you can observe, Mr Zheng had rejected a lot of tea from people that tried to sell them to his factory, either by commenting that the tea had no aroma, the forest tea was contaminated with terrace tea, or the tea was not from Yiwu at all. Tea lacking aroma is not uncommon based on bad agricultural practices, harvesting and processing methods today. Often or not the only way to overcome this and to make a product that is sellable, is to mix in a percentage of aromatic tea leaves to make up for the odourlessness.

Here’s a mention that the yunnanese continued to produce “mi”, which means raw rice for their own consumption, and at the same time they produced “fan”, which is cooked rice for the hongkong consumers.

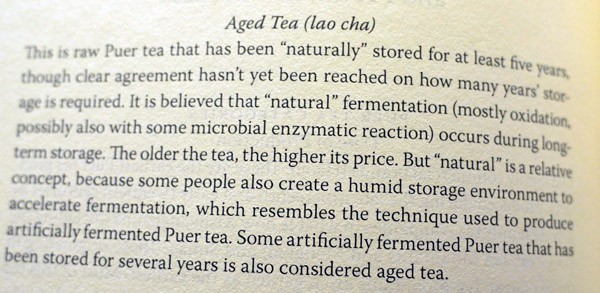

The importance of distinction between oxidation and microbial fermentation is made here. Actually I think fermentation is a horrid word when used in describing tea for many reasons. Oolong teas are lightly oxidized to mid high oxidized, they are not “fermented” i.e. you dont let bacteria and fungi grow and act on the tea! but yet right now many people confuse the terms and tend to combine both the words oxidation and fermentation in the tea trade. It is essential to distinguish them if you wish to take tea appreciation to a higher level. Oxidation is just chemical changes, fermentation is action on something by bacteria or fungi, which may secret some kind of enzyme or by products from digesting the tea which gives it a particular type of flavour that may not exist in normal oxidation.

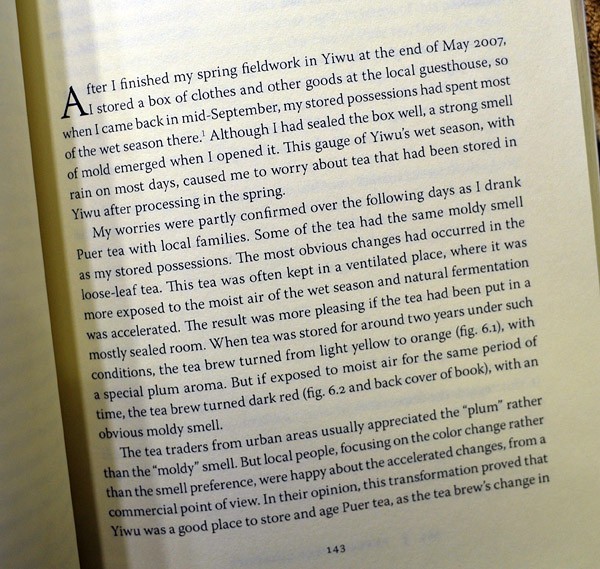

More importantly is the opinions of the yunnanese on sealed storage, as mentioned here, that the tea, when sealed in a storeroom/warehouse in adequate quantities, may allow the development of new oxidized notes, fruity plum aromas etc, whereas in moist storage it would take on a moldy aroma. They want to achieve oxidation, not fermentation.

So, is sealed storage something that was eventually invented by people recently, or was it something that the yunnan people had knew about a long time ago? I would think the yunnanese did know it early, they had been harvesting and consuming pu-erh teas for over a thousand years perhaps, and the rest of the world, only for the past fifty years. There is now two ways to pu-erh tea, one way being the hongkong warehouse style, the other, the yunnan “sealed” style.

Is sealed storage the way to go? Drinking mostly sealed stored teas right now, I’m in good opinion that this method could be good. IF you want tea to become hongkong style, you dont need top quality tea leaves!! If you read Deng Si Hai’s book from 2004, all the famous labelled teas, famous guangyun tea cakes, they were all made from not high grade tea leaves, generally coarser ones like grade 3, grade 4 and lower. With the current craze on old tree/ancient tree pu-erh, where precious aromatic and fragrant large shoots and leaves are harvested from giant trees, why expose the tea cake to allow the aroma and fragrance to be lost, to pick up warehouse notes or damp notes? These real ancient tree pu-erh cakes can be incredibly pricey, from hundreds of dollars per cake to thousands now.. is there any sense to treat them in an hongkong style?

Also, people debate about humidity and create pumidors just to ventilate and keep a certain level of humidity, worried that the tea cake would dry out. Imagine you have a sponge that contains 20% water, you seal it up in a mylar bag or a ziploc bag and impulse-heatseal the plastic, the sponge will still contain 20% water no matter what. This is the same with tea cakes, if you seal them with the right moisture level, they wont go moldy, there is sufficient water content for it to age, and by sealing, you trap and keep all the precious aromatic molecules in! There is no need to let the tea cake be exposed to high humidity levels just to regulate the water content if you get it right early.

But will sealed storage improve all teas? unfortunately not.. there are many selection criterias that you might want to consider that will only confine successful sealed storage to a small proportion

1) The leaf quality, if its pure strain ancient tree, unmixed with terrace, has good aroma, fragrance, that would be an excellent candidate. Tea from spring would be much better as well.

2) The leaves must be sun dried in the maocha stage,and not dried by hot air or oven baking. If the tea is made in the wrong season, rains and bad weather would complicate the process, resulting in the pursuit of alternative drying methods

3) The tea cake must not be over-compressed

4) There must be sufficient moisture in the cake, it cannot be absolutely dry. Perhaps so far from experiments it seemed that many of the delicious sealed stored cakes had a moisture content of around 10-12%.

Once these parameters are fulfilled, you may have considerable success in a few years when your tea matures with decrease in bitter notes, the appearance of juicy fruity notes, and a thick salivating yellow to orangey brew. If it doesnt achieve that in a few years, which could mean that the leaves are not pure, not processed properly and adulturated etc, you can then transfer it to a hongkong warehouse for damp storage to get the musty notes.