A large piece of fragrant wood drifting ashore onto Awaji Island in the 6th Century, and presented to the Empress Suiko was recorded in the Nihon Shoji. The ability of Prince Shotuku to identify this fragrant wood as aloeswood or Jin-Koh, suggests that this material had already been known by the royalty in Japan much earlier than recorded.

As Japan does not produce any aloeswood at all, it is apparent that there should had been trade and communication between the island of Japan and the outer world, China, Asia, Southeast asia, for these fragrant materials to be known and to be imported. Sino-Japanese trade dates back to the fifth century and perhaps earlier. Buddhism was introduced from China during that time, and together with it, came the introduction of incense use, which subsequently evolved into profound incense culture.

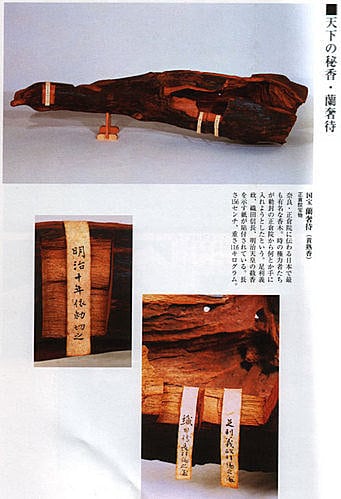

The Ranjatai, an 11.6 kilogram (1.56 metres long) piece of aloeswood, is perhaps one of the most famous pieces of fragrant wood in the history of Japan. Originally named ōjukukō (黄熟香), it was an Imperial tribute item from China to Emperor Shōmu (AD 724-748). After being transferred by order of Empress Komyo to be was kept in the Shōsōin (正倉院) treasure repository belonging to a powerful and influential Buddhist temple at that time, Tōdai-ji in Nara, it was renamed Ranjatai (蘭奢待). It still remains in the Shōsōin treasure repository today, which is now managed by the Imperial Household agency. The words 蘭奢待 contains 東大寺 in its structure.

For the past millennium or so, small pieces were cut from the Ranjatai. Notably one small piece in 1465 ordered by Emperor Gotsuchimikado as a gift to Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa, in 1574, a small piece from Emperor Oogimachi to general Oda Nobunaga for his efforts in unifying Japan, in 1602, Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu whom was powerful and influential enough to obtain a piece, and in 1877, when Emperor Meiji asked for a piece. It was said that Oda Nobunaga kept only a small bit of his piece for himself, and gave the rest to worthy men under him, including tea master Sen-no Rikyu, whilst Emperor Meiji broke his piece into two, one for keeping, and another which he burned to enjoy the fragrance.

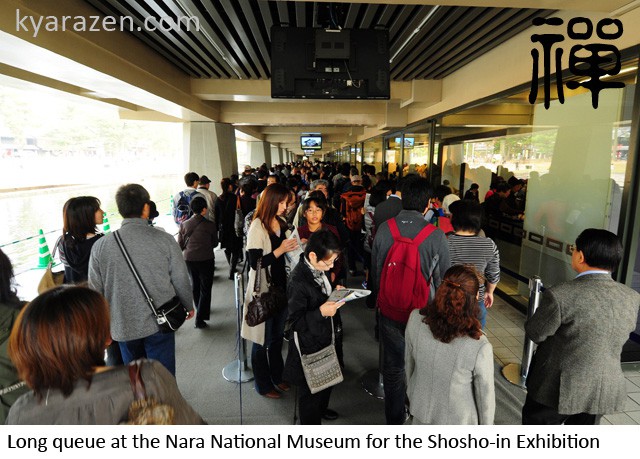

The Shōsōin holds over 1000 items, many dating back to the Tang Dynasty (AD900+), of which approximately a tenth of the items are selected for exhibition annually for a short two weeks before the onset of autumn, a period of time when both weather, temperature and humidity conditions are good. Most items would only be exhibited less than ten times per century, and before its re-appearance in 2011, the last time Ranjatai was exhibited was in 1996.

I was there at the exhibition at Nara National Museum in Japan in 2011 to see the Ranjatai in person. The queue to see the exhibition was incredible, it took over an hour of queuing just to get into the museum, it was so crowded that people jostled each other along as they were viewing the different exhibits. Unfortunately the Ranjatai was kept in a sealed glass showcase, and I was unable obtain a sniff of it myself.

Under strict classifications, Ranjatai is NOT kyara, despite many online sources claiming it to be. The Ranjatai is officially classified as ōjukō, or yellow ripe aloeswood. However, it has been historically recorded, and said by many to be exceedingly fragrant, with some even describing the fragrance to be perfect, flawless. Having not sampled nor smelt it personally, I can only imagine that it should be indeed very fragrant for it to reach such legendary status over other existing pieces of aloeswood both in the Shōsōin and throughout Japan.

Within the Shōsōin collection there is another piece of agarwood, very much less famous than Ranjatai known as Kou-jin, and it is a piece of 栈香, at over 16.5 kilograms, 1 meter long. This was last exhibited in the 2008 Shōsōin exhibition.