春茶苦,夏茶涩,要好喝,秋白露.

There is a frequent saying amongst generations of Chinese tea drinkers that : Spring tea is Bitter, Summer Tea is astringent, Autumn tea is the most delectable. 春茶苦,夏茶涩,要好喝,秋白露.

This has been mis-translated by many, and together with the omission of the fact that this saying only applies to Tie Kuan Yin and not all the teas. Due to these mis-conceptions, most people would jump to conclusions and quickly assume that Autumn tea is the most sought after since it is the most aromatic/delectable due to this saying.

The truth is that Spring tea is generally the most sought after by experienced tea drinkers, not autumn teas, due to Spring tea’s more “complete” taste characteristics. You can think of expensive sought after spring flushes of Dragonwell, Bi Luo Chun, Pu-erh Gushus, high mountain Taiwan teas. In the art of tea, the pursuit is not simply the strongest aromatics, but a balanced brew, aromatic enough, body is full enough, with sufficient and right after taste. Autumn tea can have delicate, clear aromatics, but the lack of body and a weak after taste is less preferred by experienced tea drinkers. Instead, autumn teas can be well liked by new-comers to tea as many people start off appreciating tea from the aromatics.

A nice analogy would be just dropping a slice of lemon peel into water. You get aroma only, whilst the aroma may make the water more enjoyable, imagine having some lemon juice, some sugar inside, a bit of carbonation, and the drink is now tasty.

In oxidized teas such as Oolongs/Tie Kwan Yin, spring tea is generally made with a lighter oxidation, whilst autumn tea is more heavily oxidized in an attempt to fatten up the body and improve the presence of the after taste. This is no “secret” if you refer to old published literature, or to know it straight from the experienced tea merchants that had been in the business for many decades. With careful oxidation and processing techniques, autumn tie kwan yin can become as delicious and just as sought after as a good spring tie kwan yin, with top grades of both named as “Cha-Wang”. 茶王.

In pu-erh tea that is not oxidized, the tea is blended instead, i.e. some spring tea with loads of autumn tea. Don’t be dismal to discover that most of your favourite pure “Spring” pu-erh tea cakes from merchants that so call “hand processed” the tea themselves are heavily blended with autumn maocha to tone down the bitterness of the cake, and improve the receptivity.

Why is Spring Tea Bitter?

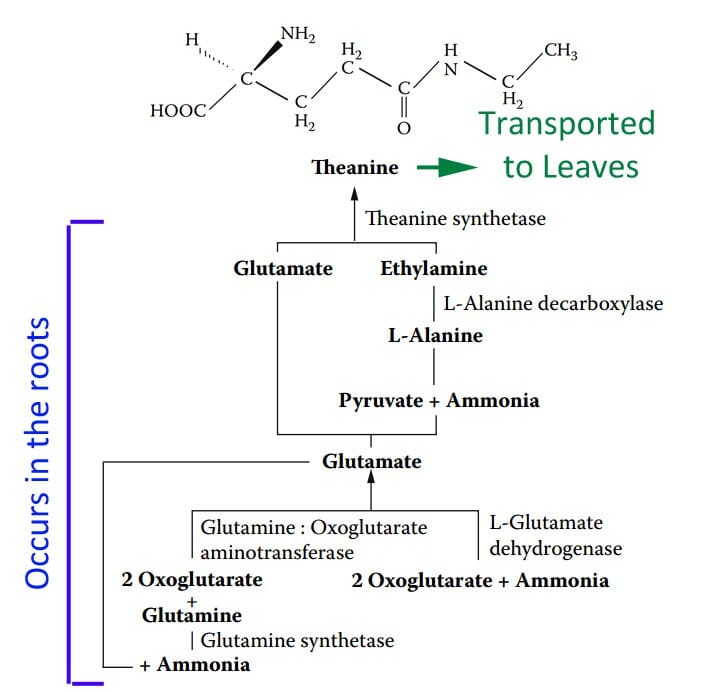

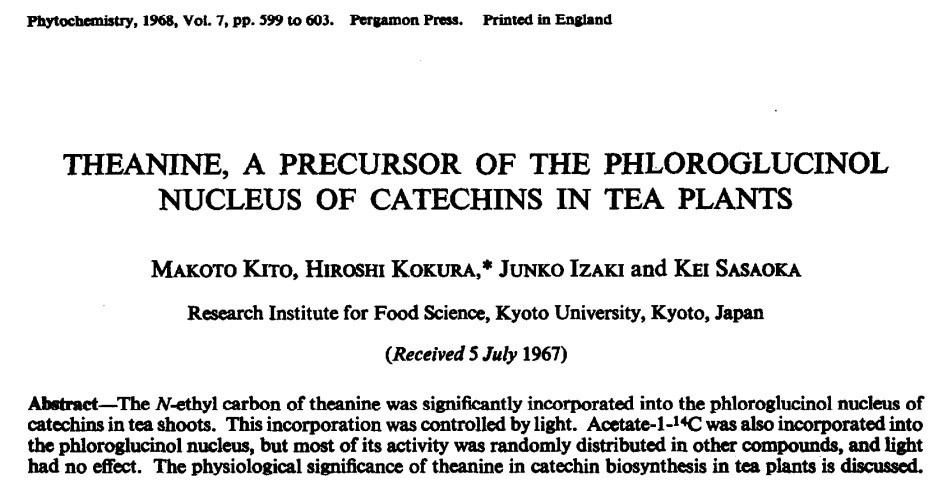

The bitterness of tea leaf directly correlates with the intensity of sunlight it is exposed to. The Japanese discovered this very early, and thus Gyokuro was born, shade grown green tea that tastes sweet and creamy, umami. When the Japanese became scientific and evaluated gyokuro by research methods, it was revealed that theanine was the major contributor to gyokuro’s taste characteristics. In the presence of strong sunlight, theanine is converted to polyphenol/catechins with positive correlation in levels, i.e. stronger sunlight, more conversion, vice versa. These polyphenols/catechins are bitter tasting compounds.

Another interesting fact is that all the theanine in the tea leaf is produced by the roots of the tea plant! We can easily assume now that small tea plants with small root systems, versus gigantic roots of ancient tea trees, there will be difference in theanine production capabilities, but that will be a topic for further investigation in future write ups.

In late autumn and winter, with little sunlight, many of the tea plants get a chance to “rest”, and allow for the accumulation of nutrients and theanine/theanine precursors. Autumn is the season for senescence, the plant withdraws nutrients from the leaves and apexes and puts them into storage to prepare for the coming winter. In traditional Chinese medicine, herbs that are storage organs, i.e. ginseng roots, etc are best harvested in autumn. In Spring, the season for proper growth and rejuvenation, the tea plant mobilizes its storage reserves and pushes all the nutrients to the apexes for the leaves to bud and sprout. This will also result in seasonal difference in tea taste.

To guide you through the seasons, we can consider the following

1) In Extreme early spring, before the first sprouting of buds, the tea trees/plants have been in quiescence throughout end autumn and winter, sunlight is little, short in duration, temperatures are cold. The plants had spent the quiet time preparing itself for the upcoming season of growth.

2) The first buds of spring come when the temperature is right, and the sun is gentle. The tea plant would have mobilized quite some theanine to the tea buds and leaves in preparation for the increase in sunlight intensity in due time. Due to low sunlight, little theanine is converted to bitter polyphenol catechins, so the high proportion of theanine allows the tea leaf to taste sweet, creamy, umami. If you shade the tea buds at this point of time, like you do with gyokuru, this characteristic can be extended for longer durations through spring without the tea becoming bitter.

3) Towards mid spring, the tea leaves start to convert more and more theanine into bitter polyphenols to protect itself from the increasingly strong sunlight. The tea becomes more bitter.

Why are polyphenols important for tea leaves?

a) Because they act as “sunblock” for the tea leaf, preventing the leaves from being scorched. The benzene ring structure absorbs light in the range of 250-260nm, which is the wavelength of UV radiation. So by accumulating large amounts of polyphenols in the tea leaf, the plant is able to protect itself by dissipating energy through the UV absorbed by these compounds.

b) They have antioxidant properties that protect the leaf against photo-oxidative stresses and photo-oxidative damage from the sun.

4) Spring is the season for many flowering plants to flower, and allow the tea to pick up nice aromatics. If you do not believe how efficiently tea can absorb smells, just leave a pack of your favourite tea exposed in the refrigerator overnight and you will be able to taste/smell different items in your fridge in the tea’s brew.

5) Tea has two type of aromatics, one type is the aromatics that come from the external environment, i.e. surrounding flowers, camphor trees etc. The other type of aromatic is from the nature of the tea, from the tea plant itself. Good teas are prized for the existence of these two type of aromatics in the tea, turning the tea into something more experiential. Aromatics are precursors to experiences. In my comparison of tea and incense, I found that incense tend to focus on the 意境, which is the imagination, the smell/aroma re-creates places, takes you on journeys. Tea, for the accomplished masters, is the focus on 心境, the inner state of oneself, i.e. stillness, oneness. The taste of the brew has a “grounding” effect on people.

6) Summer tea becomes extremely astringent and bitter due to extreme sun, and extreme high levels of polyphenols. These teas are harder to get a tasty brew from them. When steeping the tea, before sufficient aromatics come out into the brew, the bitterness and astringency can be rather overpowering already. If you have sufficient understanding of “gongfu” tea, you might be able to circumvent this problem, that will be something covered in other write ups in the distant future. During this intense summer, any theanine produced is quickly converted to polyphenols which are further conjugated amongst themselves to form more complex polyphenols.

7) In autumn, finally after the intense exercise of theanine production, polyphenol synthesis in combat with the strong sun, the plant can finally heave a sigh of relief when light starts to fade. The soil can also become nutrient depleted as the roots of the tea plant had been constantly absorbing nutrients, fixing nitrogen, throughout spring and summer.

8) The plant having expended huge amounts of theanines to be converted to polyphenols in summer, now does not maintain high levels of theanine, but from late autumn to next year’s early spring, it has now time to recuperate.

9) Lower sunlight in autumn results in teas that have lesser polyphenols as the season progresses, the tea can be rather easy to drink with little or no bitterness. Due to the lack of flowerings during autumn, you might not be able to get certain “spring flower” notes in the tea. In Oolong tea, certain floral notes can be obtained through post processing, i.e. controlled oxidation of the bruised tea leaves. However for pu-erh tea that is not processed the oolong method, with the presence of many huge camphor trees in Yunnan, these teas can easily absorb quite a load of camphorous notes.

10) Autumn tea, with less bitterness, can be brewed more intensely that other teas, i.e. pushed with longer steeps, more leaves, with no severe bitter in the brew, this allows for more aromatics to be extracted during the brewing, giving drinkers the impression that autumn tea is more aromatic.

11) Autumn tea is also very much more “woody” lignified, the leaves can be papery for oolong, the stalks are stiff and woody for pu-erh. More lignified the tea leaf/stalk is, the more able for the tea to withstand scorching hot water! Autumn teas can take a more intense heat than spring tea. Spring tea is tender, and can easily become vegetable soup.

Lignification

What is lignification? It is the chemical process by which plants, secrete lignin-alcohols and other chemical compounds to saturate the cell walls of certain plant tissues to make it stronger. If you chew a piece of pear and find grits, these grits are actually lignified sclerids. If you bite into a stalk of celery, and have these tough long stringy fine threads that are present, these are lignified tissues. Lignification is the process by which tender green materials become stronger, become woody, and that is how wood is formed, with the lignification of xylems in secondary growth. (Paper is made from wood, I’m mentioning it here so that you will link it to a pu-erh storage concept later).

Apart from taste differences, there are anatomical differences between spring, summer and autumn teas. Spring teas are tender buds, they have soft, floppy, juicy stalks due to low lignifications. You can imagine a little shoot or sprout from a seed, its always tender. The leaf structure of early spring buds are also rather low on venation, juicy and plump.

In autumn, as the tea plant has gone through successful cycles of leaf growths, the stalks of the tea leaves become tougher, woodier. The coloration of the fresh leaf will also be slightly duller compared to the bright green of spring, together with coarser leaf veins and a more papery texture to the leaf.

How does all these tie up with pu-erh tea?

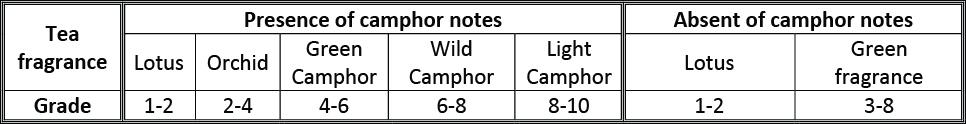

Simple. Here is a quick outline of Deng Si Hai’s Book on Pu-erh tea that came out in the 90s. Some collectors consider this book to be “evil”. It was a book that led many people to fantasize about owning the rare teas pictured, to the extent of going crazy seeking out to own these old teas, and occasionally falling into dishonest vendor traps; the vendors probably studied the book and details well enough mimic and fake some tea. There are other recent excellent writers on the pu-erh subject that also criticized some of Deng’s writings, but on the whole, what Deng had written is a nice summary and a guideline to pu-erh, especially on the aging aromatics. In combination with some materials from other writers, these are the known characteristics to the aromas of aged pu-erh :

Lotus fragrance is always typical of aged sheng pu-erh that is made of fine tea buds, usually grade 1 leaves. Famous teas that are known to have this fragrance is the “Da Kou Zhong”, so sought after that one cake is in the range of 4-5k USD now. Other similar teas that have this lotus note is bai zhen jing lian. For sheng pu-erh, many years of proper aging is needed for this note to appear.

Orchid fragrance, this commonly comes about in the famous red labels of the fifties and beyond. A bit more damp storage after the tui-cang process can also result in the chance of orchid fragrance appearing. A classical example would be the original 7532.

Green camphorous can be found in 50s pu-erh tea cakes, tiebing etc. 40s Ke Yi Xing also has very much green camphorous notes.

Wild camphorous notes can be found in hundred year old Fu Yuan Chang, thirties Dingxing Hao round tea, Tong Qin Hao round tea, Song Pin Hao round tea, red, green labels also have very clear wild camphor notes.

Light camphor notes are found in compressed teas of other shapes such as mushrooms etc.

Un-accounted for aromas by Deng that are now discussed in modern pu-erh appreciation :

Dates taste – light oxidation big leaves, well aged not in warehouse, can develop red date taste, i.e. 7581

Ginseng taste – big green rough leaves into damp storage, or slight damp storage old ripe tea, most of the aroma comes from the twiggy part of the tea, i.e. 8592, 7562

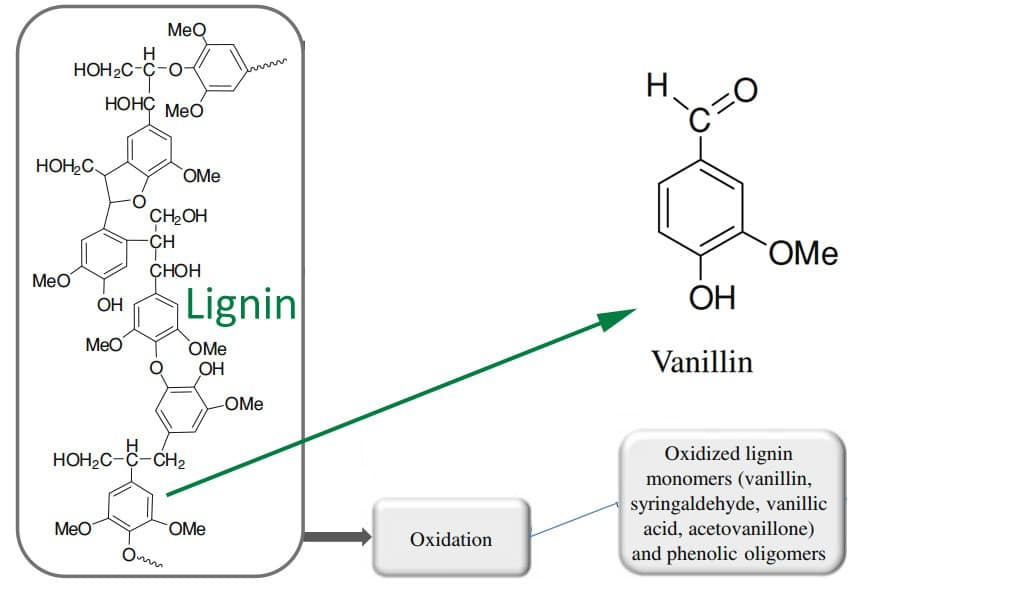

The Scent of Old Books – Vanillin and related compounds

The old book-ish scent of pu-erh tea is often desired by many whom are new to pu-erh and subsequently led to think that all old pu-erh must have the old-bookish scent. The old bookish-scent in pu-erh can be considered to be one of the characteristics of a HK warehouse note, achieve through warehouse storage methods in Hongkong.

Some authors mention that putting tea into a HK storage process is the best way to get these notes, and that without warehousing, but self storage, it can be difficult to achieve.

Consider the old library scent, and the scent of your own study at home, if you have enough books at home that are old enough to get that old bookish scent in your study, maybe your chance of success with getting the same notes in home puerh storage will be there.

Why does these teas all develop to give old bookish scents? Apart from aged pu-erhs such as 7572, 8582, other old teas like 50s Qian Liang Cha, 70s CR Fuzhuan tea, Fang Gourmet’s 1979 Tiao Suo red tea, also have this note.

If you observe the leaf structure of 7572, 8582, or some of the other old teas, you will realize that they contain rough, bigger leaves, and twiggy stalks. Rough big leaves and the twiggy stalks are more lignified than tender leaves, just like how wood is lignified. These lignin in these rough leaves and twiggy stalks will age, oxidize and break down to give vanilin and other compounds characteristic of the old book taste. This suggests that the paper used to wrap the tea may also have an effect, so will the bamboo leaves used to wrap the tong, as the lignin content in these materials will break down over time, liberating vanillin and other notes that will be absorbed by the tea contained within.

Whilst the old book taste is enjoyable, food for thought, how about aging some white paper for decades just to get the old book taste? Is pu-erh all about achieving the old book taste?

With advancements of “sealed” storage methods when it comes to pu-erh, there may be a chance in the future that people will get to taste complex, delicious aged teas that are not overwhelmed by the old book scent, nor the vanillin and other bamboo notes from the wrapping materials.

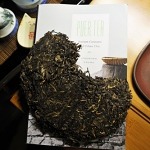

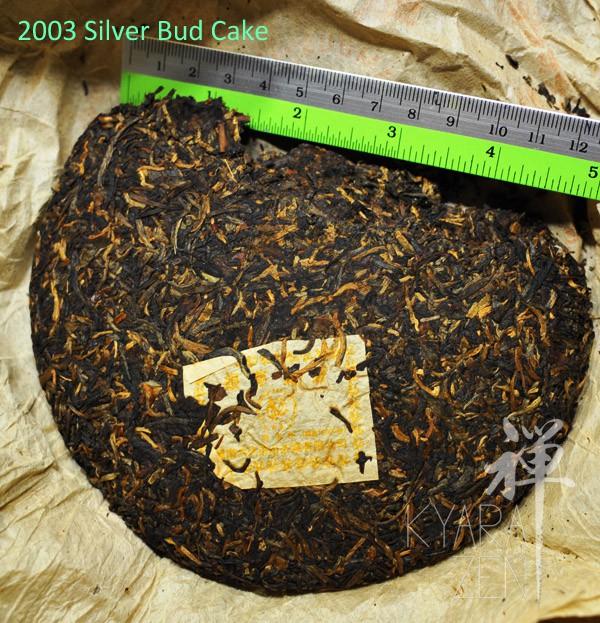

The 2003 Silver bud tea cake pictured here does not contain any twigs nor lignified leaves, mostly tender buds, and after 11 years, is developing traits of a nice lotus leafy fragrance, with no traces of old books. I’ll be revisiting the tea in the future years to come. It was with regret that I was much less knowledgeable about tea 11 years ago than now, if not I would have bought a huge truck load of these tea cakes.. which was just a few dollars a cake then… 🙁

Tea Blending

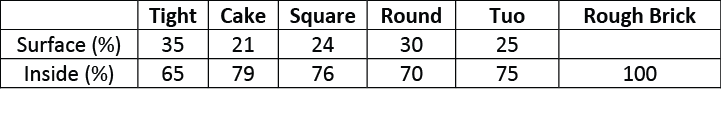

If one does an analysis of old tea from the previous century, you will observe that surface and internal tea leaf grades are different.

Many Tea cakes are blends, i.e. 7542, everyone probably thinks of it being first made in 1975, but it actually was designed in ’75 but first produced after 1981. If your vendor sells you a 70s 7542, please give him/her a little kick. 7572 was one of the first four teas produced since 1975 and predates 7542 in production. There is also a current misconception is that the whole 7542 tea cake is made of grade 4 leaves. It actually is a blend of grade 3 to grade 6 leaves. Grade 3 for front and back surfaces of the tea cake, and grade 4-6 sandwiched in the middle. This is how Menghai and many tea factories had been doing so for decades.

This will create an interesting complexity in the tea from the blend, since finer leaves are less lignified, may have the chance to develop orchid and lotus notes, whilst the coarser woodier leaves will develop some old booky characteristics, together with the camphorous notes if present. This is why some of these old teas can be of certain value due to the classical complex nature of their flavours attributed to leaf blending. Spring and autumn tea blends will also age with unique complexity as autumn tea is much more lignified.

Nowadays, many modern pu-erh tea cakes are pure single top grade compressed into one whole tea cake, the complexity in them will not be a result of blending, but its own aromatic aging characterics. Spring gushu cakes don’t have much lignified twigs as well, mostly tender green leaves. I’m full of anticipation on what proper gushu tea will age into through proper storage in due time.

What is good complexity then? Its may be up to the drinker to decide. But if you are intending to invest in pu-erh, then you have to know what it takes to get a final aged product that will taste good, and will be sought after by collectors.

At the end of this article, you can now attempt to understand why Lao Ban Zhang 2007 is such a sought after tea, with its price jumping to almost 5.5k USD in just a few years. Strong aromatics, strong bitter, nice umami taste. The good soil, good weather, and good root system of the old trees of Lao Ban Zhang had allowed for a strong accumulation of theanine in the tea, and with a good proportion converted to polyphenols in the spring sun, giving a very full balanced taste. The tea is so concentrated with these compounds that quick steeps is all it takes to get good brews, you don’t have to push the tea, the tea pushes you instead. With over-harvesting, now the old trees are increasing injured, tired, the soil is getting depleted of nutrients, the recent harvests of Lao Ban Zhang in 13, and 14, pale in comparison as compared to that of 07.