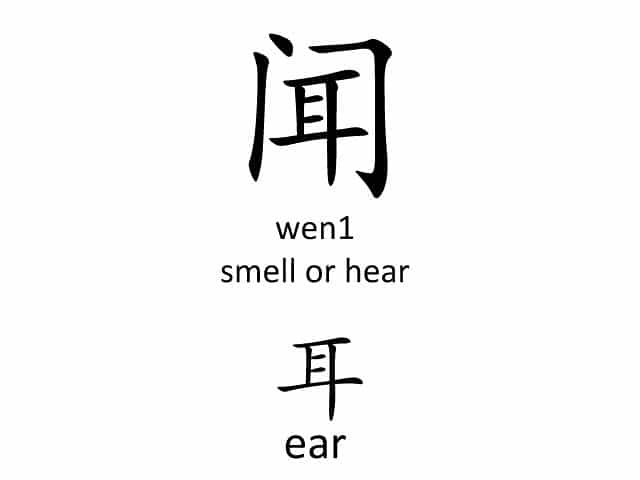

闻, or 闻香 (mon-koh), can be literally translated as to smell or to listen to fragrances. This is probably why the Chinese word for the action of smelling, contains a character representing the ear. Most people would have expected a nose instead of the ear.

Asano Michiaki of the Kaori-Bunka (an Incense culture research society in Japan) published in 1995 an extremely interesting diagram where he associate certain fragrances with musical notes. I personally go through similar processes when reviewing incenses to help derive the descriptions that I would write under the “listen” classification in my reviews.

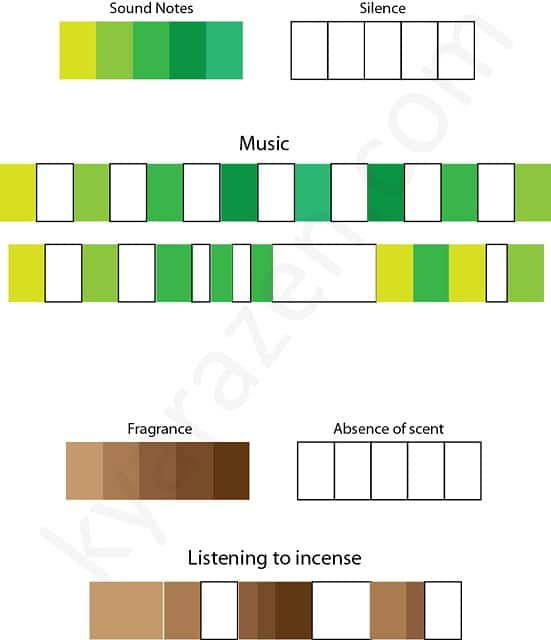

There is an underlying similarity in concept in the enjoyment and interpretation of fragrances and music. Music comes about when a bunch of sound notes are arranged in different orders, and most importantly separated by different amount of silence. The silence is as important as the sound.

As such, in fragrances, the “absence of smell” is just as important as the smell itself, this allows for maximum contrast. It is no surprise that top end incense sticks, such as Shoyeido’s Translucent Path, Gyokushodo’s En-no-Sho, Yamadamatsu’s Shuju Kyara, Seijudo’s Kyara Enju etc, are very stoic and composed incenses. They do not blast the air with constant intense puffs of fragrances, but instead, weave slowly and delicately between the state of scent and scentlessness, a very middle centric path with a sense of wabi-sabi.