Every yixing pot collector probably would have heard of the legend of seasoning yixing pots, that the longer you use it, one day, by just adding hot water to the pot, you can get tea! It is a myth and a huge misconception, partially due to poor translations of chinese texts.

The original historical phrase was along the line of : 紫砂壶的特点是不夺茶香气又无熟汤气,壶壁吸附茶气,日久使用空壶里注入沸水也有茶香; This roughly means that the unique feature of yixing zisha pots is that it does not rob the tea’s fragrance, neither does it cook the tea leaves, it picks up the qi of the tea over time and after a long period of usage, if you add hot water into the empty pot, you can liberate some tea fragrance.

You get a whiff of tea fragrance, not a brew from an empty pot. You are not supposed to expect tea stains to dissolve to give you tea!!

Over a period of usage of your yixing tea pot, you may realize that the pot can develop a nicer patina over time and become glossy in appearance. How long does this process take? For some pots it can be achieved in a week or two, for many pots.. up to month or years, and for some.. almost never at all!

Pictured here is a 70s 线圆pot, one of my favourite shapes. This particular pot was initially dull, but the patina developed quickly within a couple of weeks of daily usage brewing all sorts of random teas.

Both pots pictured here were used for a month each, brewing all sorts of random teas daily. We can see that the pot in the foreground was developing some shine (which will probably take a few more months of usage to improve), but did not achieve the same sheen and glossiness as the pot in the background. They were from the same era, of the same material, same firing method, almost the same weight (which means same amount of clay). The only difference was that the maker was different. If you tap both pots, they have almost the same pitch/tone, suggesting similarity in the degree of firing. So, what can be the difference that lead to difference in patina development?

This pair of pots were manufactured in ’89 from an excellent clay blend. The pot on the left saw a month of usage, the one on the right for only a few days.

What you have seen here are probably the very few “success” stories that I had when it came to Yixing pots. Out of all the pots I had encountered or are in my collection, under 5% of the pots are like this. For the lucky ones, maybe a higher percentage, and for the less lucky collectors, maybe one in a hundred pots. Then upon further investigation and research for the past few months, I had started figuring out how/why the patina develops, and certain selection criterias which increases the chance of selecting a “good” pot.

Just testing out my theory/concepts in a recent purchase, here is a pot, just 2 weeks old in my collection, used daily for random teas. The rate at which the patina developed was rather surprising.

What happens to Yixing pots when one brews tea in them? The pot expands with hot water added, and it contracts when the tea is dispensed, the empty pot allowed to cool. This is most easily observed if you brew tea in a good shuiping pot or similar, where you can block the airhole. When hot water is just added, the airhole “closed” you will see the liquid in the spout of the pot almost at the edge of spewing out/overflowing, but in the next five or seven seconds or so, it gets “sucked back”, the level falls. This is simply because the pot had expanded, and now there is half a cm^3 increment in overall volume.

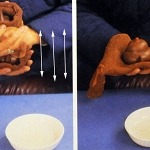

This may just simply be 0.5ml but in terms of expansion, it can be quite significant to the overall surface of the pot. This pot expansion can also be observed by looking at the picture below, a hong ni Xian Piao empty (left), and filled with boiling hot water (right). The color of the surface deepens. This phenomena is reproducible with many hong-ni pots from all different eras with the following observations; the bigger the pot, the more obvious the color deepening. The more the pot has been used, the faster the color deepening response is, almost immediately when hot water is added into a seasoned pot, versus a couple of seconds of lag for a new pot.

What is happening on the surface of this pot? Whilst the surface of the pot looks smooth to our human eyes, under a high resolution microscope the surface is rough, it is like an undulating mountainous terrain with mountains and valleys. When the pot has hot water added, the mountains move apart, the valleys become wider, this results in a colorimetric change that is most obvious with red clay.

An image from airpano.com, of China’s Guilin.

With regular usage, even with just hot water alone and no tea used, a pot can start developing a nice patina. This is due to the repeated expansion and contraction of the pot surface, micro particles can fall off, making it smoother with some shine.

It gets even better when you use tea! Tea interacts with the clay, with some of the tea compounds possibly binding to the clay surface. Some of the minerals present in the water can also bind to the clay in micro quantities. After some usage, take a cotton cloth and give the pot a nice rub, you may see the patina becoming even more glossy. This should not be really attributed to “tea stains”, Yixing pot seasoning and patina development is not about getting thick tea stains on the pot. A lot of tea stains does not contribute to the best patina, if not the interior of all pots, which is always more heavily tea stained, would turn glossy. Just a tiny invisible bit of tea and tiny invisible bit of water staining, coupled with a good clay surface, with repeated expansion and contraction. That’s all!

What determines a good surface then? This was revealed in some contact angle goniometry experiments on pots that developed patina quickly and pots that didn’t. It is a very simple technique with a simple goal, to determine the surface wet-ability. The higher the wetability, the broader the angle, as a water drop smears and flattens on contact, the lower the wet-ability, the rounder the water drop. Some of the very best pots showed low wet-ability when the pot was cool with droplets running off, and when the pot was hot (at 90-95 degrees celsius, similar to that of hot water), the surface became very wet-able. In layman’s terms, when cold, the valleys and the mountains are compressed rather closely to each other reducing tea or water binding, and when hot, the space created by expansion between the valleys and mountains renders the pot much more wet-able.

Shao Da Heng’s 大亨掇只壶

Why does such surface characteristics happen? It is a reminder of Gu Jing Zhou’s writings. Gu, had deep respect for Shao Da Heng of the Qing dynasty and spent many years studying the rare existing pots of Shao. In Gu’s own words, Shao had achieved “perfect” firing for all his pots, every single item studied was just perfect. In the seventies, when Gu was guiding his students in clay processing, one of the steps involved the pounding of the clay dough. Strangely, this step was incredibly important to Gu, a couple of his students (王洪君/沈遽华) had taken a huge mallet and pounded the clay for many hours, to which when Gu saw the clay he lamented that the clay had been pounded to death!

What he actually might had meant was the right amount of air to be pounded out from the clay and homogenizing its distribution, it must not be excessively pounded that the clay becomes fused with low porosity with all the particles crushed. It must not be under pounded that the clay is too porous. The well pounded clay must be able to “live”, it can breathe, it is homogenous and it has good propensity for expansion evenly.

A sponge ball exhibiting primary porosity.

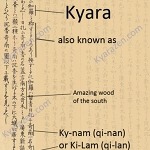

Yixing clays having dual porosities. What dual porosities mean, can be explained by a simple analogy. Imagine a box containing round sponge balls. Each of the sponge balls have tiny holes in them that allow them to absorb water. These tiny holes are known as “primary porosity”. Secondary porosity refers to the space between the balls of sponges. So in yixing clay, the clay particles are porous themselves, and when the clay is kneaded and pounded into a dough, the spaces of air/water between the clay particles are secondary porosities. Secondary porosity is determined by the maker’s clay pounding and processing, and is the major determinant in whether a pot would develop a patina fast.

Gu’s dedication, meticulousness, focus, gave him a legendary status in the Chinese Art world, non yixing collectors similarly would be smitten and awed by the beauty of the pots he makes. Here is an example of a Sunflower themed pot, with perfect clay, perfect firing, incredibly beautiful patina.

The long story short, here is probably what most readers would be most interested in, tips on pot selection.

1) Avoid hollow feeling, low tap tone pots, chances is that the clay has too much air, and the firing may not be optimal

2) Avoid pots that are sandpaper rough. It is ok for the pot surface to feel a bit rough here and there, but it must be mild, reasonably gentle. If it feels sandpapery rough, the clay is probably under pounded.

3) Choose good firing, not overly bright like glassy metallic ring which suggests over-firing.

4) Pick a pot with reasonably density, not crazily heavy as though the pot is cast iron, but not one that is super light

5) Know the approximate optimal firing colors for each clay. Well fired hongni usually takes on a nice red color tone. if under fired, it would be rather orangey, and if over fired it may be dark red.

6) Surface characteristics, sprinkle some water on the surface of the pot to see its wetability. If it wets extremely well when the pot is cold, the clay is sub optimal, potentially too porous. If it wets well only when hot, you’re in for a good treat, this pot will shine extremely quickly.

7) Choose pots from the right era. Pots of the 70s, which are fuel-fired in tunnels, together with the excellent clay during that time, often season and develop the patina really effortlessly.

8) The larger and flatter the pot, the easier for patina to develop! This has to do with temperature maintenance, and also the larger scale expansion and contraction during repeated brewing.

9) Avoid polishing pot surfaces with sandpaper or other materials, this breaks the skin of the clay and will lead to poor seasoning. Once surface is sanded, the only other way out is just to keep polishing until it becomes shiny like many pots from thailand.

10) After using your pot for a month or two, when the pot is dry, buff the surface with a cotton cloth and see if the patina becomes gloss deep. Do not let thick, unsightly tea stains or water stains build up, that is not real patina.. just tea stains.