This is the fourth article of the Methods of Tea Brewing series.

Teochew Nang, Ka Ki Nang, Pah Si Boh Xiang Gang! 潮州人,家己人, 打死不相干.

Its a funny greeting but if you are of Chaozhou heritage use it whenever you encounter a stranger from Chaozhou, there’s this immediate bond forged, a sense of good will and friendship. The phrase literally means ChaoZhou people, we’re our own people, and even if we beat each other to death its no big deal.

I’m from a pure Chaozhou heritage, with my ancestral roots in Ampou, Swatow. Many times when I attempt the Chaozhou Gongfu brewing method for tea, it fills me with some kind of nostalgia, a wish that my grandfather was still alive to have tea with me. He absolutely loved tea, but had passed away even before he could smell retirement.

If you might have noticed, I had not used the word “gongfu” with any of the other tea brewing methods posted, but only with the Chaozhou one. This is because “gongfu” brewing used to refer to the Chaozhou brewing method specifically. Its a little queer whenever people talk about how they would “gongfu” a tea, and all they are doing are just multiple steepings of different durations, which can simply be done with a tea bag.

The Chaozhou gongfu tea brewing style (CZGFS) probably dates back a few centuries ago, with the popularization of small pots. Theres some argument around by different “tea scholars” that the brewing style dates back to the time of Lu Yu in the Tang Dynasty, but it is unlikely. Some of the water boiling methods, the optimum temperature for brewing i.e. crab eye sized bubbling, the use of a charcoal stove known as a 风炉, tea refreshing by baking or re-roasting in Chaozhou brewing style may have been adapted from Lu Yu’s Cha Jing. In the Tang/Song dynasty, the dominant brewing style still involves grinding/milling tea leaves, cooking the tea into a soup with added spices and herbs.

Gongfu means skillful. The Chaozhou brewing method earned its “gongfu” title because it was a method that was originally developed for the brewing of low grade/coarse teas, creating delicious tasting brews through skillful brewing.

If you go on tour in China, you may chance upon the chinese tea ceremony, which sometimes they will describe to tourists as the gongfu tea ceremony, with pretty ladies brewing tea gracefully, lots of fancy names to the various fancy steps, it is actually an amalgamation of various traditional brewing styles together with adaptations from Lu Yu’s Cha Jing. These fancy steps are now being “canonized” as Gongfu tea but whether it actually is, it remains to be debatable.

The Chaozhou brewing method that I’ll be describing is the basic method that is commonly used by people in the streets. There are more advanced and refined forms of this method, but the core philosophies and principles are similar.

To first understand CZGFS, you have to understand the following principles.

1) Tea leaf quantity and swelling

2) Tea Leaf loading and steep durations

3) How to Savour. The proof is in the pudding, whether CZGFS works or whether you have done it properly, the main judgement is on the taste of the brew, not how well you have done the rituals for years.

Tea Leaf Quantity and Swelling

It is not uncommon to use high leaf to water ratio, i.e. 1g per 10ml, as CZ tea drinkers like it strong and intense.

To infuse tea leaves, and create the brew, as per described in a previous article, tea leaves need to absorb water, allow the tea compounds to dissolve, and to allow these compounds to escape the leaf into the water.

This is an example of 7 grams of Wuyi Yancha in a beaker, occupying around 60ml of space. When doused with hot water and allowed to swell freely, the total amount of space needed for the tea leaves to swell maximally, is around 110ml.

So what happens if one squeezes 7g of tea leaves into 65-70ml pots?

If squeezed in, brewing in these small tea pots, the tea leaves cannot swell fully, thus limiting the amount of water that can be absorbed by the leaves. With limited amount of water absorbed, the amount of tea compounds dissolved from within the leaf into the brew becomes reduced. Remember that in a previous article I had written that oolong tea leaves have “dried tea juice” coated on the outside of the leaf? This tea juice on the surface is not affected by the need to swell as its on the surface and can be dissolved. The result of this is that the brew is made up from dissolved dried tea juice together with contributions from dissolved compounds from within the tea leaf.

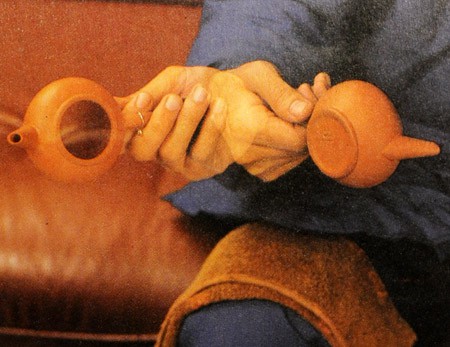

This would further imply that pot shape and tea leaf loading quantity controls how a tea is brewed. With variation in shape and height, it will determine how much the leaves can swell, creating different brew profiles. The flat Xian-Yuan pot on the extreme left does not allow the leaves to expand much upwards, and with a compact interior, tea leaves cannot swell very much at all. Conversely, the Xian Piao pot that is 2nd from the right, has a rather round interior, this can allow tea leaves to swell rather fully and the brew will contain much more dissolved tea compounds from within the leaf. There’s good and bad to this, without enough tea compounds dissolved from within the tea leaf, there is insufficient 韵,but if the leaf quality is low, over swelling or full swelling of the leaves will lead to bitter astringencies coming into the brew quickly. The pot on the right is too tall and as such is not appropriate for CZGFS.

Tea Loading and Steep Duration

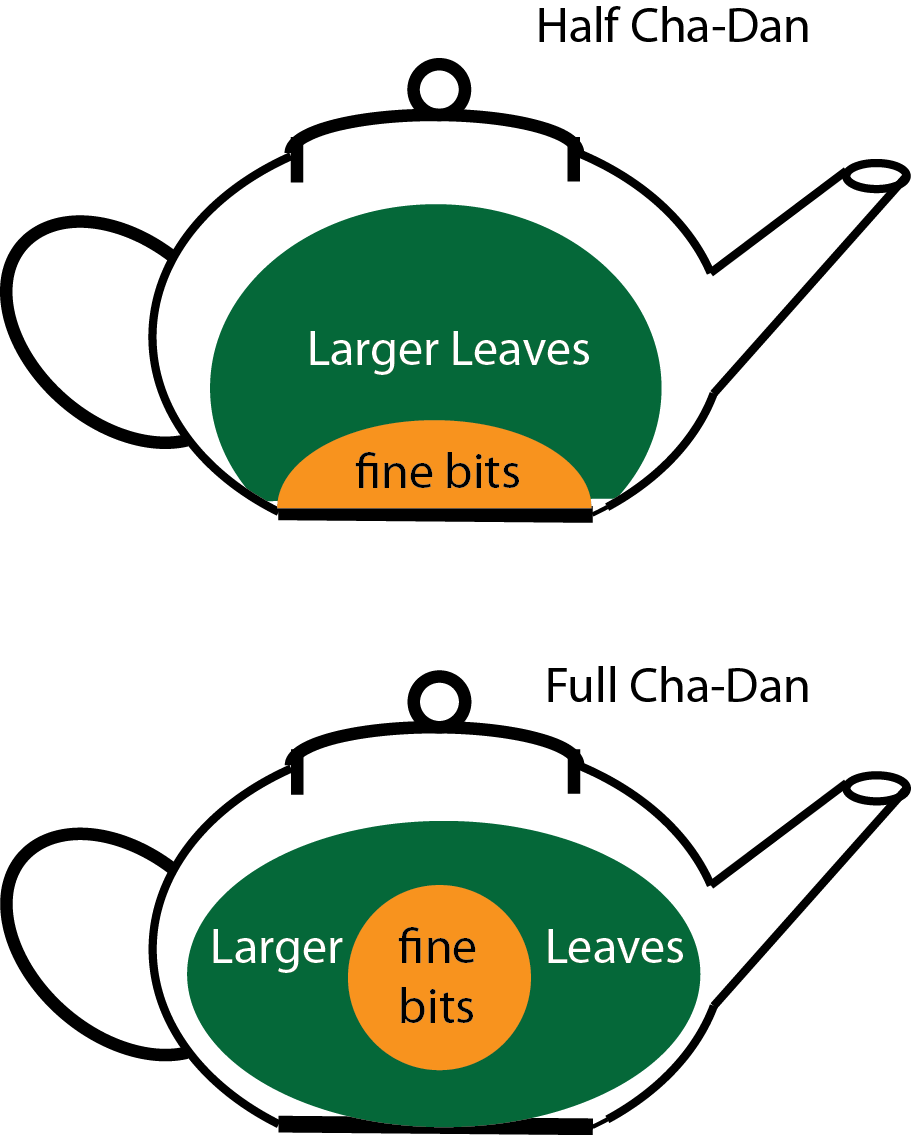

The tea pot is usually loaded to 80% full with regular grade tea with the tea leaves forming a “ball” or a “tea gall”/Cha-Dan 茶胆 within the pot. The tea leaves in the pot is referred to as a “gall” as a gall bladder holds bitterness within itself, and it must not be broken. Once broken, extreme bitterness will appear. The Cha-dan is formed by random loading leaves into the tea pot, allowing them to form a natural interlocking mesh. The fine bits should either be at the bottom of the pot, or loaded into the middle of large leaves. This is achieved by loading large leaves with an empty hole in the middle, loading fine leaf bits into the middle, and then filling up with large leaves again. The fine bits can either be natural crushed leafs found in the middle and bottom of a container of tea, or can be obtained from hand crushing some larger leaves.

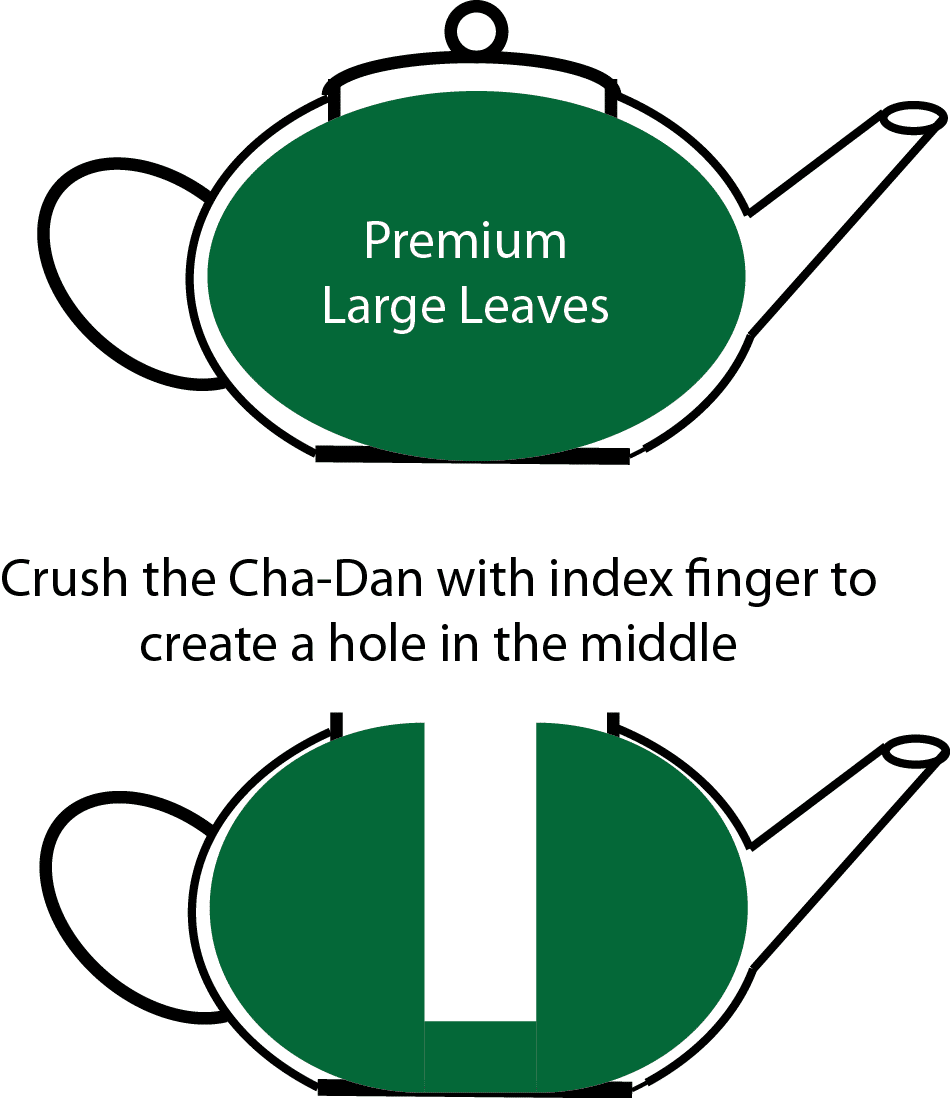

In some refined forms of CZGFS, where leaves used are of rather premium quality and the whole container of tea is all “whole” leaves, one can consider loading a pot fully with leaves, and then crushing a hole in the middle with an index finger to create small leaf bits and to create the 20% space needed for the leaves to expand. The amount of space can be arbitrary and calibrated based on one’s experience and preferences with the tea. The small leaf bits created in this process will also be fast infusing, and can contribute to the brew’s profile.

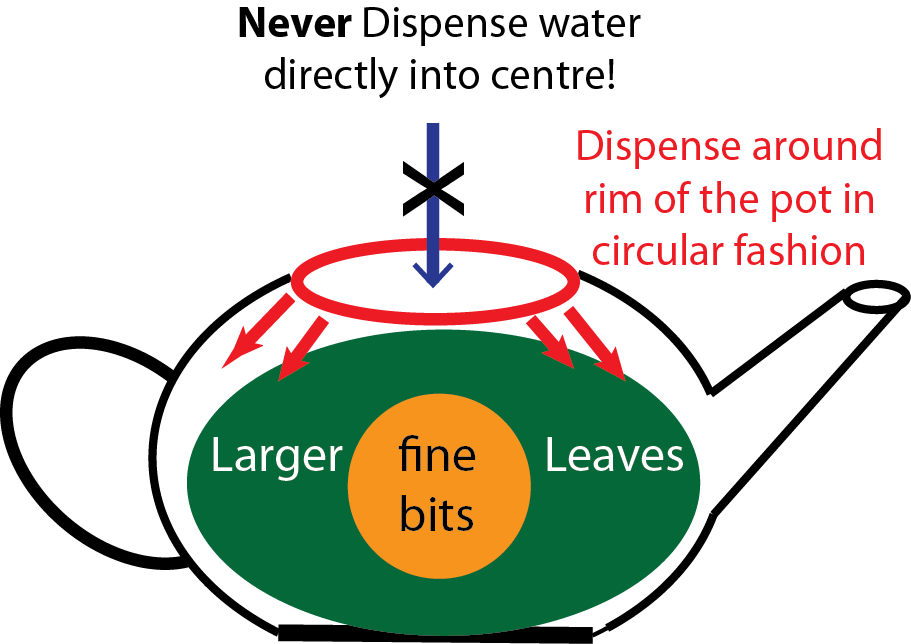

In dispensing hot water to make the brew, one must never pour hot water directly into the middle of the Cha-Dan, which will cause the brew to become overly bitter. Instead water should be added in circular motion around the periphery of the rim of the pot, and to be done quickly.

Steeping Duration and the Brew

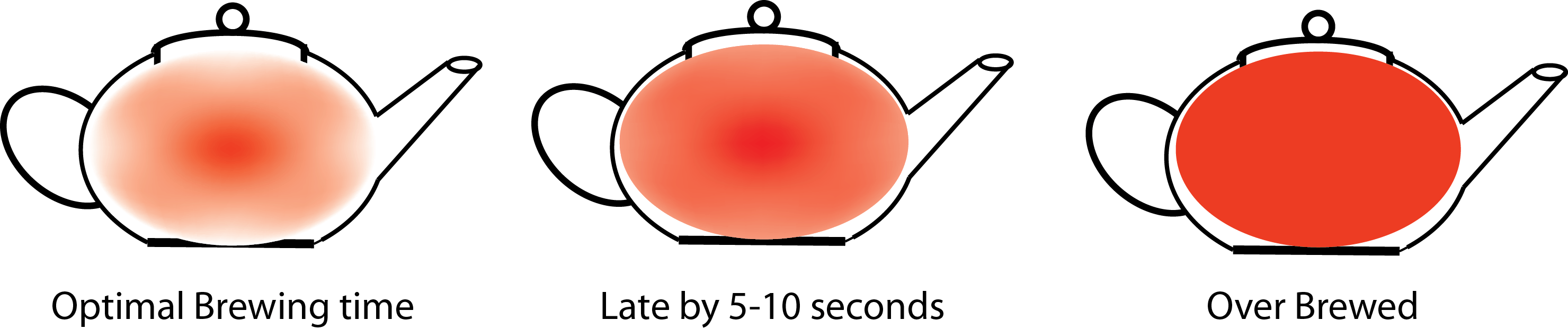

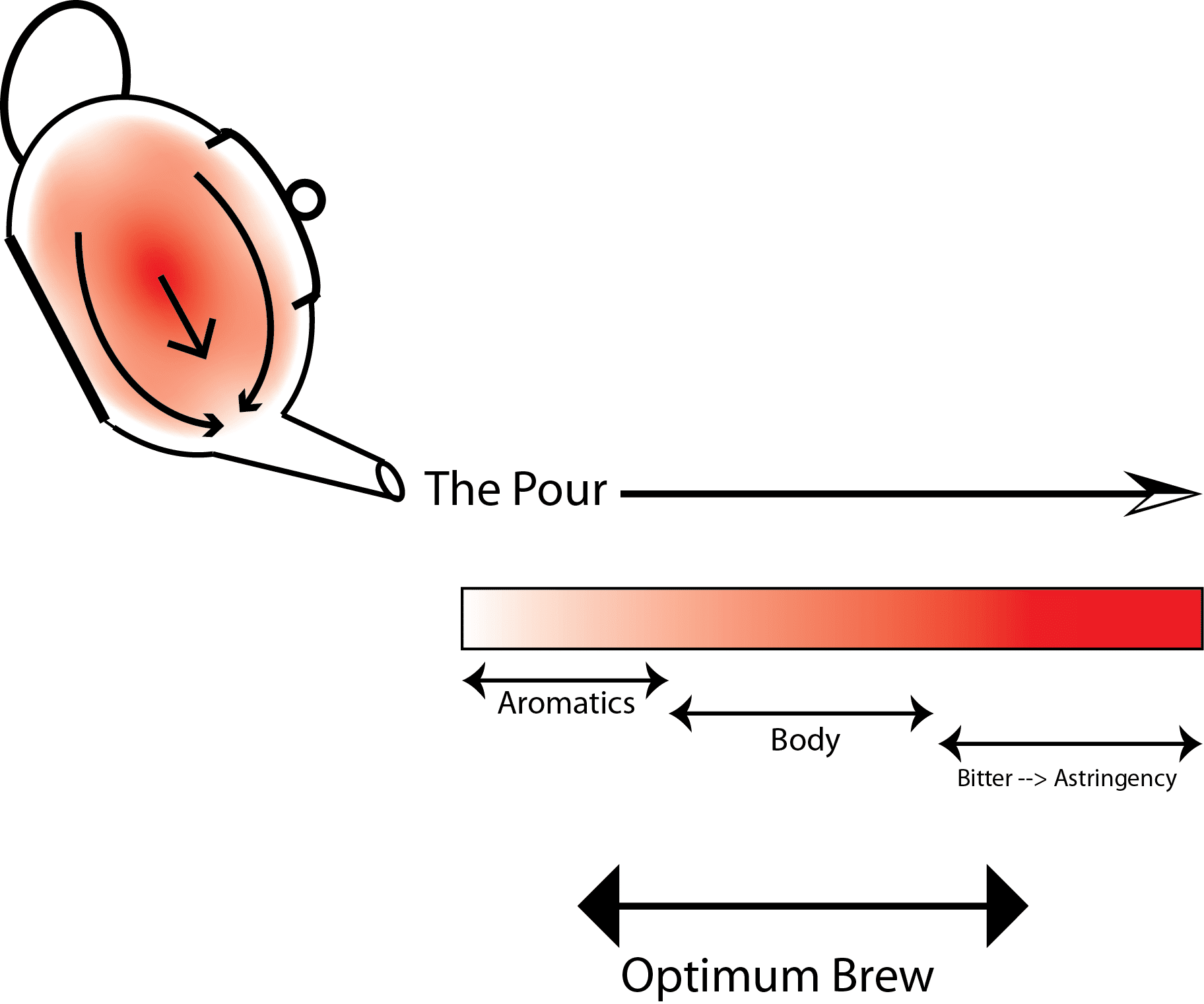

CZGFS has one of the shortest steep durations ever! Usual steeps are very quick, a matter of several seconds to ten seconds etc, depending on the tea and the brewer’s calibration. As such, pots must have very quick pours. If a pot has too slow a pour, the tea that has not been dispensed yet would have become over-brewed. In advanced CZGFS, one may encounter tea masters or brewers that discard the front or the rear of a steep, collecting only the middle portion during the pour, this is because the tea master/brewer knows the tea well, and knows how to concentrate the best components of the steep, getting rid of flawed portions.

Savouring

A common saying for CZGFS, 初喝嫌其苦,久喝嫌其韵(味)不足。

When new to CZGFS, drinkers will think the brew to be too bitter and strong, but after drinking this style for a long time, one will seek stronger flavour and Yun, and will always criticize teas that are insufficient in these aspects.

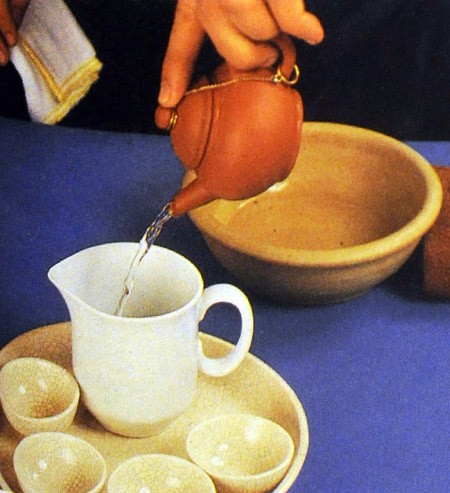

In CZGFS, savouring the tea brewed by this style is usually done in tiny thin egg shell like 25ml cups. These cups should be dispensed to exactly 70% full, below which, the brewer is considered stingy, and if too full, its considered to be bullying and not respecting the drinker (cup will be too hot and full to be picked up).

Bringing the cup to the lips, the tea should be sipped without the lips touching the cup! Instead using a upward air “sucking” motion, the tea is sipped and drawn into the mouth. This aeration process helps the aroma to bloom and fill the mouth and nasal cavity. The brew should be good enough to make the mouth feel comfortable, rich, full, and the throat to be comfortable with subsequent hui-gan.

The above are the core principles of CZGFS proper, many parameters mentioned are arbitrary and depends on the brewer’s calibration and preferences. If one desires to have mastery over CZGFS, there is careful consideration required of these various factors/principles.

Traditional Chaozhou Gongfu Style – the original “Gongfu” tea brewing method

Over the past centuries of CZGFS, there are many variants of CZGFS with added or reduced steps, despite the procedural differences, bulk of the principle/philosophy are identical.

The original CZGFS was developed on the basis of brewing tea that was rough and coarse, mostly Wuyi Yancha, dancong. Rolled teas are usually not used. The brewing process must be undisturbed, and it must align the three aspects of 精, 气, 神. Essence, Qi, and Spirit. Tea ware requirement is more specific, the movements are decisive and non-slipshod. Its said that the stringency of Chaozhou brewing of some schools of thought is almost as strict as that of the Japanese approach towards tea brewing procedures and ceremonies.

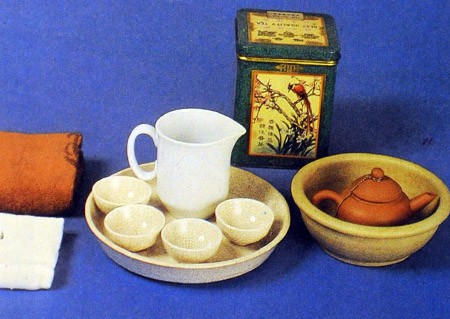

1) Tea ware preparation and preparation of brewer

- Focus, attention, quietness

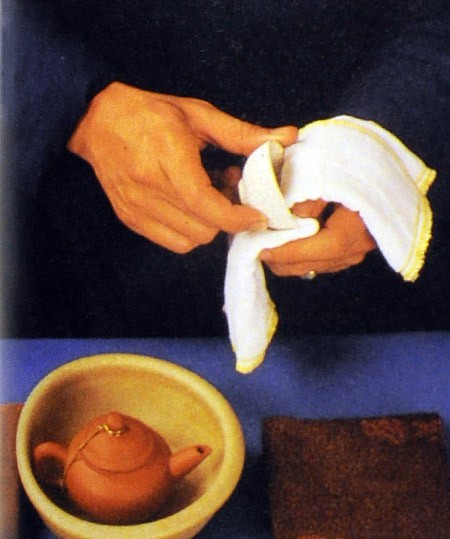

- On the right thigh one puts a cloth for wiping pot

- Left thigh a cloth for wiping cups

- On the table two square clothes, in the centre is a deep tea reservoir

- Pot is preferably more porous, lower fired

- Lid should be very fine and fitting well

- Not too big pot, there is a limit as CZ brewing insists on 3 cups

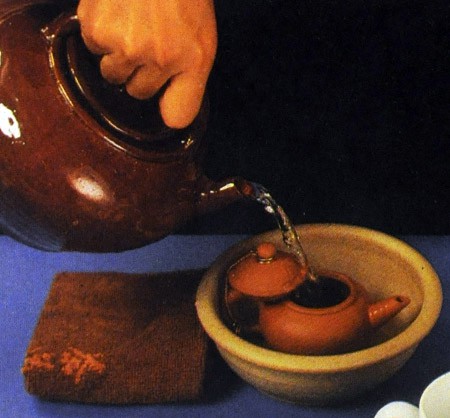

2) Use boiling water to heat the pot and the hot water is to be discarded into the fairness pitcher.

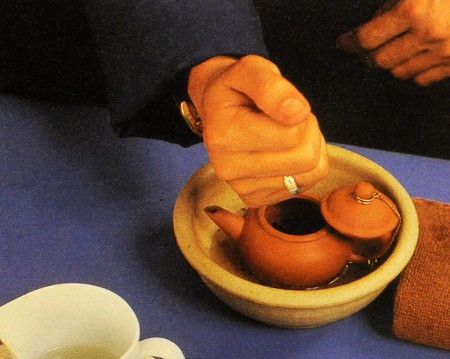

3) Dry the pot. Whilst many high end teas use the damp warming method, chaozhou uses dry warming method. Tap the pot on the cloth on the thigh to get rid of excess water. Fan the pot until the pot is totally dry

4) Adding of leaves usually to be added to 80% full. Formation of a “cha-dan” or a gall round ball structure in the pot by loose random loading.

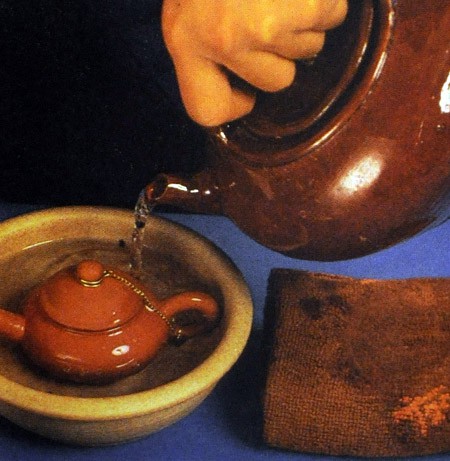

5) Baking the tea. One can either bake the tea in the pot. For rough tea or old tea, or aged tea, to remove dampness and other unwanted scents, and to refresh the tea, pushing the aromatics to the surface. Important for the pot to be well made, so that when hot water is doused on the outside of the pot, with the air hole closed, no water will enter the pot. Whilst the tea is being baked by the heat, the cups can be pre-warmed with hot water.

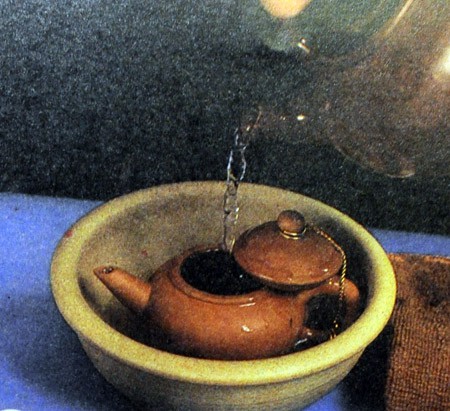

6) Adding hot water to the brim carefully, in circular motion around the mouth of the pot, minimizing direct pouring into the centre of the chadan. Use the tea pot lid to scrape off froth if any, and the lid to be put on quickly. The first steep is to be discarded, considering it a process of washing the tea leaves. Hot water is immediately added after the wash step, creating the first Brew. Water should be just off the boil with reasonably small bubbles, and not an aggressive rolling boil.

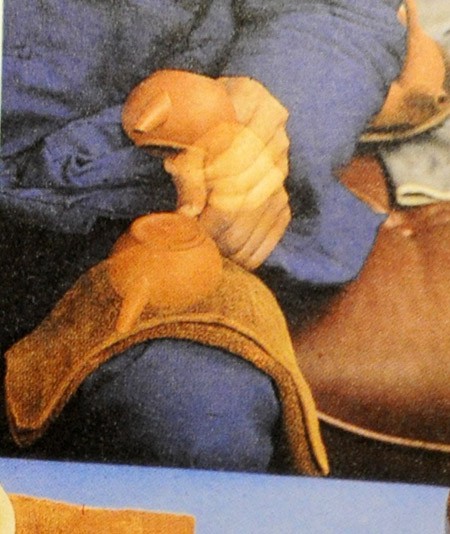

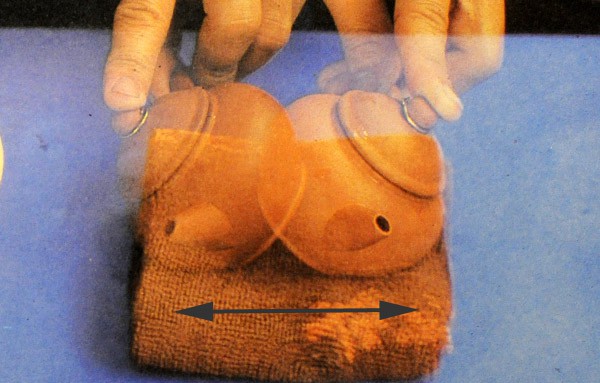

7) Rocking the pot. Lift up the pot onto a cloth on the table and shake with a finger blocking the airhole. Left right motion, first brew do it 4 times, 2nd brew 3 times, and each subsequent brew minus one. The rocking helps get the “tea juice” and aromatics off the surface of the leaf fast, and the tea is dispensed before the bitter astringencies come out from within the leaves.

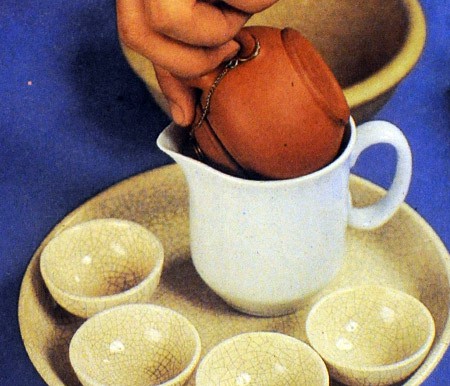

9) Dispense into a pitcher. Repeat the steeps for 2 more times. After that, dispense tea from the pitcher into cups for the guests.

Tips

1) Very old tea is afraid of long steeps, it becomes sour and bitter

2) Baking or refreshing tea leaves in a roaster can decrease the margin of error in CZGFS. By using a roaster on a ethanol flame, one can bake off undesirable sour notes, and also by baking, the tea aromatics are pushed to the surface of the leaf, and the bitterness within the leaf will drop a little.

3) Shaking must not generate froth, if not it will over-extract

4) Aim is to get the “surface” juices off

5) Prevent over swelling of the tea leaves. Full unrolling of leaf is not achieved nor necessary

6) CZ brewing style stops at 3 brew. Each steep must be even or equal, as such one’s attention must not change nor be slipshod.

7) The pot must not be too big. Generally the size limit for CZGFS might be around 150-160ml. Anything bigger, the thermal properties are hard to control, the pour is not fast enough to dispense everything in due time, leading to brewing mistakes.

8) A common chaozhou variation is to dispense into 3 cups only, as 3 cups make up the word Pin 品,which means to savour. The brewer will also choose to discard the front or the back of the brew or even customize the brew for each person depending on how much of the front, middle, rear or the brew goes into each cup. If customization is not done, the brewer will dispense in circular clockwise motion around the 3 cups, dispensing them evenly

9) Water boiling can be done using a side handled, white clay Chaozhou kettle on olive pit charcoals. This will enhance the tea brewed, adding depth.

This is the fourth article of the Methods of Tea Brewing series.

The following articles are part of this series: