In the Chinese Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD), the stick incense was invented. Dried herbs were blended, ground into powder, and mixed with binder powder, the powdered bark of the Machilus Thunbergii tree which acts as a glue when wet. The resultant dough could then be extruded or rolled into sticks, and allowed to dry in a cool dry environment.

The Edo period in Japan (1603-1867 AD) was the period where incense sticks appear to be first made, although it wasn’t extremely clear whether they had developed it on their own, or that they had learned some of the stick making skills from China. There are several aspects that could provide evidence that the Japanese had their own way of making sticks, these square cut sticks. Traditionally, these sticks would be made from flattening the incense dough into a sheet and cutting the flat sheet into individual strips/sticks. This method is not seen nor recorded in Chinese historical records/literature. Also, the making of incense using the needle like leaves of coniferous species was also not seen in Chinese incense.

In modern day, the cutting of flat incense sheets into square sticks is no longer done. Most Japanese companies do retain the square cut of these incenses as a mark of its heritage, but all of them extrude their incense with a hydraulic drive machine. The advantages of hydraulic extrusion is a more compact, stronger stick that is not brittle when dry. By traditional cutting, the lack of proper high pressure compressive forces on the incense dough made the sticks rather brittle and hard to handle.

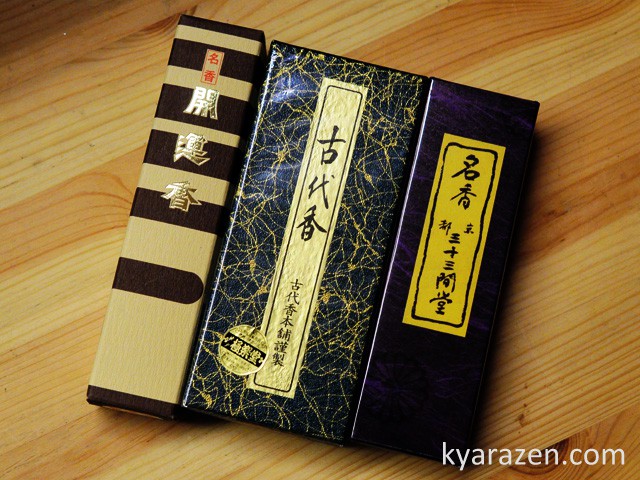

Although there are quite several square extruded incenses on the market, this time I pay particular attention to these three incenses from three different companies that have a rather “similar” olfactory profile.

Brand : Baieido – Kai Un Koh, Kida Jinseido – Kodaikoh, Sanjusangendo Incense

Source : Purchased from Japan

Price :

Kai un Koh 840 yen / 40 sticks (USD $8.50?)

Kodaikoh 1200 yen / 67 grams (100-120 sticks) (USD $12?)

Sanjusangendo 700 yen / 80 sticks (USD $7?)

Amount Burnt so far prior to this review :

Kai un Koh 1 box

Kodaikoh Approx 20 sticks

Sanjusangendo 1.5 boxes

Taste profile :

Kai Un Koh Spicy +++ Sweet : + Bitter +

Kodaikoh Spicy : ++ Sweet : ++ Bitter +

Sanjusangendo Spicy: ++ Sweet : + Bitter + Salty -/+

Scent characteristics :

Kai Un Koh, Kodaikoh, Sanjusangendo ( similar for all 3 incenses) :

Texture – Bold, smooth, voluminous, intense

Binder notes – well concealed by the herb and spices used, almost as though the binder was one of the useful notes

Intensity – +++

Focus : Strong diffusive

Listen :

Kai Un Koh

A drycool desolate breeze across warm desert sand.

Kodaikoh

the clear voluminous voice of kabuki theatre

Sanjusangendo

The warm hearth of a charcoal fire heating a cast iron kettle in winter

Difficulty Level :

Low intermediate for all 3.

Incense perception distance : 60 cm away

Review :

There’s pretty much a scent/olfactory overlap amongst these three incenses. I had given several sticks to friends, in unlabelled tubes as part of an experiment, sometimes they mistake the Kodaikoh for the Sanjusangendo, other times they mistake the Kai-Un-koh for something else. Once you’ve spent enough time with these three incenses, the Kai-Un-Koh can appear to be a lot more distinct, whilst both Kodaikoh and Sanjusangendo can be rather similar. All 3 incenses can be quite intense, and just a couple of inches indoors is sufficient to scent a small room.

In the olden days, floral essential oils were not commonly available nor used in China nor Japan in incense, and most early incenses were purely blended from spices and herbs, many made available through the silk road. As such, one can detect a clear line of clove, cinnamon, star anise, as a dominant base in all these incenses. Kai Un Koh has the strongest clove, chinese patchouli and camphor notes. It is also the driest and the spiciest amongst the three. If you reside in an asian or a chinese country, Kai un Koh will definitely remind you of this particular chinese medicine blend that people used to take for stomach problems, i.e. 藿香正气散 (Patchouli Qi restoring powder), or the modern 行军散 which is similarly crafted around the patchouli.

Both Kodaikoh and Sanjusangendo, apart from the spice base, has the licorice like bitter sweetness, with the Sanjusangendo smelling a little more “powdery” and very mildly ambery, and a little bit of saltiness.

Either of the three incenses are highly recommended for someone looking for a historical scent, a scent revolving around a strong Chinese herbal medicine core. The agarwood in these incenses are rather quiet, and dry, there are no obvious resiny agarwood notes coming out of all these incenses.

In the unburnt state, all three incenses present a very faint hint of white musk/synthetic musk, although I could be wrong. (there might be some companies that adopt plant based materials though). Whilst I’m extremely sure that historically the recipe would have called for real musk, with the scarcity, and huge expensive of real musk, it is perhaps not surprising that incense companies may end up deciding to use a synthetic.Musk is an important component of incenses since ancient times if one refers to the formulas in chinese and japanese literature. Without musk, synthetic or real, it can be challenging for incenses to have a fuller body. I’m still debating with it myself whether I should use synthetic musk in my own incenses as it is more sustainable.