As you start adding hot water to your tea leaves in a pot, could I surprise you by telling you that leaves are actually quite water proof?!

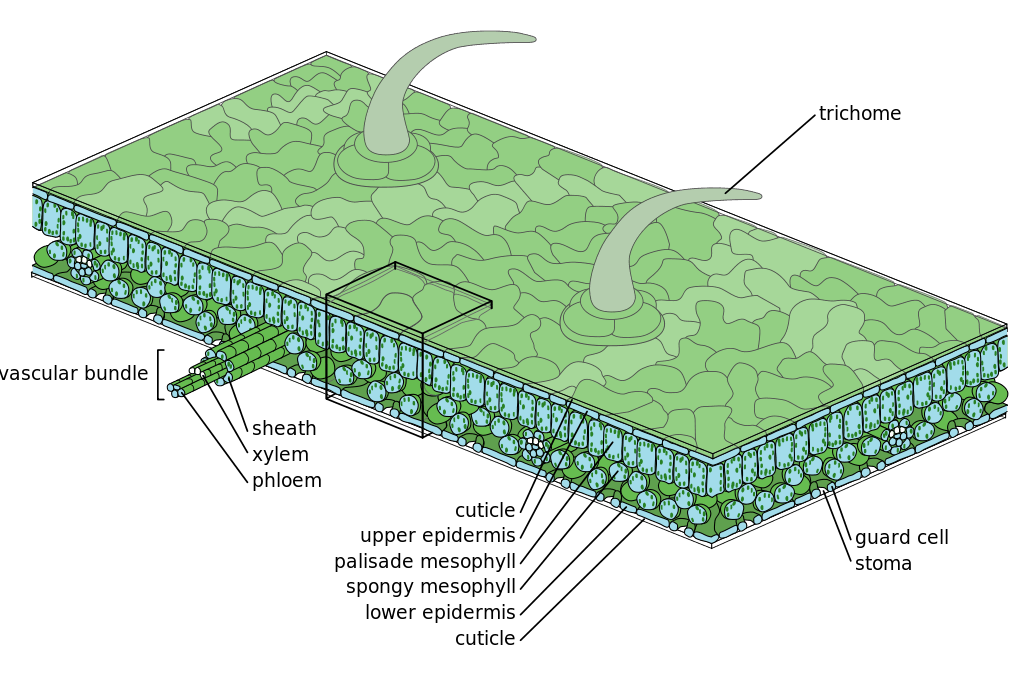

It is normal for leaves to be water proof, almost all leaves are in some way or another, this is due to a waxy layer called the cuticle that covers the surface of the leaf on both sides. Nature had made it this way, because if the leaf didn’t have this layer, it would dry out like a paper napkin in no time and the plant will die! As such, the only site of exchange that occurs on the leaf is usually through specialized cells on the underside of the leaf, the stomata.

So, when dried tea leaves are infused, what are the events that occur? Water has to enter the leaves. For green teas that are unbroken, unfragmented, water entry into the leaves would occur mostly through the existing “stalk” end, and also through the stomata. The leaves will swell, tea compounds will dissolve, and then diffuse out back into the water outside to give the brew. This process is not incredibly fast, so you may expect to steep for a minute or two starting with the dry leaf.

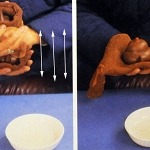

On the other hand, its not uncommon to see some oolong teas that are not rolled, i.e. Yancha, Dancong, being flashed brewed in gongfu brewing style. 5 seconds, 10 seconds type of steeping is sufficient to produce the brew. This is contributed to by two facts, one, that Oolong teas are bruised, their edges are broken, cells are crushed in some parts etc, this allow for fast water entry and fast dissolving/diffusion of tea molecules. The other more intriguing and important fact, is that Oolong tea leaves are coated with “tea juice”! This is due to the processing method, where leaves are bruised, kneaded, which results in the “tea juice” in the leaves coming out and coating the exterior of the leaves. In flash brewing, this “dried tea juice” on the surface of the leaves will dissolve and contribute. People had found it strange that I had the habit of picking an unbrewed dry tea leaf and tasting it, in principle I was actually trying to taste the “tea juice” and allow it to dissolve away before I chew the leaf and discern its contents. This has important implications in chaozhou gongfu cha, to which another article on it should be up soon.

In the recent years or so, perhaps since 2007 onwards, there seem to be changes in the way sheng-pu-erh teas are processed. It seems that somewhere around 2007-2008, sheng pu-erh tea cakes started having very fruity, oolong/fermentation type of fruity fragrances in them. Prior to this period, the sheng pu-erh cakes were more greeny, (sunlight greeny scent), camphorous, rather “high” vapory smelling than these post 2007 thick mid fruity pu-erhs.

These teas also become extremely quick-brewing, i.e. 10 second steeps and you get a nice brew. From my dry leaf chewing experiences, it becomes even more apparent that there is a manufacturing process change. Prior to 2007, leaves tend to be slower eluting, slower brewing, the surface of the leaves did not have clear/strong taste, whilst post 2007, many dry leafs have a surface bitterness and the aroma/scent came really quickly. As such, I’m now drawn to believe that extra kneading and “squeezing” out the tea juices to coat the surface of the tea leaves is now done, turning it into an “oolong-pu-erh” type of intermediate. Brewing up a quiet, light sheng pu-erh and subjecting it to thin film oxidation, one will find that the scent turns a bit sugar cane juice like, a tat fruity, hints of a “fermented” note, further substantiates this manufacturing process change. This will also allow for the formerly bitter, unpalatable gushu teas to become milder, more drinkable and having better aromatics than needing to age the tea.

Now many plantation, gushu pu-erhs of all different brands, in recent productions, have shown strong signs of this new processing method. Even a 2012 autumn gushu harvest can be processed to be just as aromatic as the spring harvest, minus the bitter.

How will these new generation pu-erh teas age? For sure many of these teas are tasty when fresh off the mill, I actually love some of these pu-erhs when they are under a year old. As they age, they reach the “ambivert” stage around seven to ten years in sealed storage, and much earlier in unsealed storage. Past this stage, when the lignin has not broken down to give the aged taste, I’m beginning to observe that these teas become really really quiet. These fruity oolongish type of pu-erh benefit best when stored like an oolong tea, sealed, away from light, reasonably dry. Oolong teas when over-exposed will lose their aromatics.

Food for thought though, the 50s Red Mark was notoriously unpalatable when young and new, which was probably why there are still surviving cakes around, if they were delicious and tasty they would have been consumed in the early days already. The 88 Qing Bing similarly was incredibly unpalatable when young and new, so bad that the story goes that the warehouse in Yunnan was full, and a hongkong merchant was asked/”begged” to take the stock over. Who knows, maybe these palatable fruity, oolongish pu-erhs can or may have the best of both worlds, extremely delicious when new, and extremely delicious when old? No one knows! perhaps only in 2027+ I’ll find out.