The Rikkoku Gomi set was first assembled around the 15th Century with the establishment of a formalized “way/art” of the Incense by founder Sanjonishi Sanetaka (1455-1537 AD), a noble under the Muromachi Shogunate of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa. Without the benefits of modern logistics, and being more isolated from the rest of the world, agarwood import into Japan in the olden days did not come from all agarwood producing countries, but only a select few.

If you look on the market now, there are expensive Rikkoku Sets from famous Japanese incense companies, and cheaper Rikkoku sets from other agarwood merchants outside of Japan, with the price difference easily over five to ten times. The difference lies in whether the wood in the Rikkoku set is “mon-koh” grade, or “soradaki” grade. Mon-koh which translates as listening to incense, is the fine appreciation of a tiny grain or sliver of a high quality agarwood, where the smell unfolds, providing one different dimensions, mental imageries. Sora-daki grade which translates as (open air fumigation), is typically normal quality agarwood without the intricacies, and is good for scenting rooms, places, clothes, with the pieces used being larger, and less resinous, less refined, many times containing some stray notes, damp notes etc.

If you buy some agarwood chips, squares from a Japanese Incense company next time, ask them whether its for mon-koh or for soradaki! Some of the very high end squares that are sold at hundreds of dollars for 5 to 10 grams, are quite refined and usable for mon-koh. It is hard to judge agarwood just by the appearance, that is, if you come across on the market a fragment of a tree or agarwood block that has a nice resination pattern on the exterior, it could very well just be sora-daki grade, don’t pay a mon-koh grade price for it! Let your nose guide you, not stories.

Some companies, just to have the Rikkoku set consistent, they only sell small pieces of woods cut from the same huge blocks that are left by their ancestors from generations ago, and thus the cutting of each rikkoku wood piece is very neat, a single block, whist others have in their rikkoku sets, wood chips that they procured off the market that are similar in taste profile, thus depending on the origin and the background of the wood, the price will differ as well when assembled into a set.

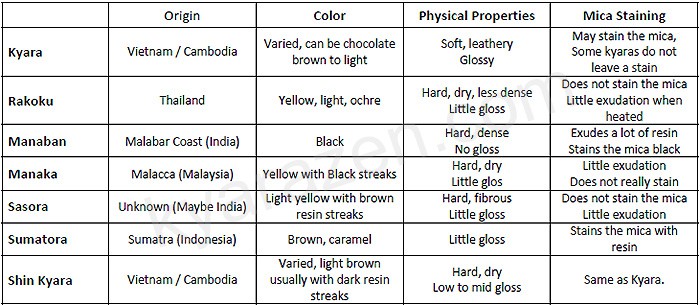

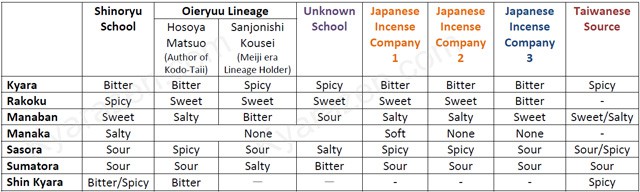

The Rikkoku is summarized as six woods from six different sources, and the five tastes – Gomi (sweet, bitter, sour, spicy, salty) is used to describe the aromatic properties of the woods within the Kit. Depending on the school, there are differences in the tastes recorded for the same Rikkoku woods, which may appear controversial. The Oieryuu school is one that emphasizes on the incense, the smell and the written records, whilst the Shinoryu school places emphasis on ko-do processes, methodologies and formalities.

Interestingly too, when I presented woods of different tastes to different people, there are some that consistently reported a different taste to that of what I and some others had perceived. These discrepancies can perhaps be explained in a few ways.

Firstly, different people have different expression of olfactory receptor types, both in receptor population and in type, and thus the olfactory profile of certain things triggers a different impression from another person with a different expression profile.

Secondly, high grade Rikkoku sets, i.e. Mon-koh grade woods, have several phases when heated the Ko-do way, i.e. Rakoku starts off bitter to me, but then it evolves into a sweetness. So it may not be conclusive just to describe each Rikkoku wood, with just a single taste if the grade is high, instead one should present both the scent profiles and tastes at different phases, and the mental imageries evoked.

Thirdly, it would be impossible to say that aloeswoods from a Single country (koku) would smell the same. Boundaries between countries are drawn by humankind, plants, trees, forests they don’t distinguish themselves as different origins. This is why many Cambodian woods can smell similar to Vietnamese ones, particularly those of high quality and of wild harvests having sweet, cool profiles. Also, within a forest, different infection mechanisms, different ages, different species, results in agarwoods with different smells. Vietnam for example, produces very high quality agarwoods that can be both spicy and sweet. Indonesia, which had barely made it into the Rikkoku with their little contribution of Sumatora, produces agarwood of all sorts of tastes! Other countries of agarwood production is also not covered, neither are all tastes complete within the five tastes.

As such, the Rikkoku isn’t a exhaustive categorization system for all agarwoods in the world, neither is it sufficient to be used for complete grading (it still can be used as a grading reference to a certain extent). The Gomi, the five tastes which can exist in many other agarwoods, even in the same place of origin. The Rikkoku set should instead be enjoyed as a “snapshot” of the high qualities of agarwood enjoyed centuries ago, and appreciated for the various imageries evoked, not only for the beautiful scent, but also the over all ko-do experience, and not to be treated as a mainstream classification system.

The Gomi, five tastes, can also be augmented to make it more complete. If one refers to old Chinese literature sources back to the Song Dynasty and before, there are seven tastes that are described. 甘苦酸辛咸涩淡,sweet, bitter, sour, spicy, salty, astringent, plain. It is strange why “shichi-mi” or seven tastes was not fully defined within the Japanese Kodo system, despite many Japanese records had described Manaka, to be soft, no particular taste, which is similar to the “plain” or bland taste of the Chinese. Additionally, when burning agarwoods from different sources, different types, it is not uncommon to come across some agarwoods that are bitter, and astringent! Unfortunately I do not have the authority, nor the qualifications to start my own Ko-Do school, but if I do, I would canonize the seven tastes. And I would also include the Chinese understanding on how the tastes evolve, which is useful in the process of enjoying fragrances, and also how the tastes curb or neutralize each other, which will be important in incense blending.

I have been asked several times by people on whether they should get a rikkoku gomi set. My advice to them was simple, get it, only if you know what you need it for, and get it if you are into mon-koh. It is not cheap, approximately a thousand dollars for maybe 25 grams of wood, and this money could have better gone into some favourite incenses, favourite perfume/oud oils instead.