Be warned! Long article ahead.. 3000+ words perhaps..

This has been one of the most difficult articles to write (although the funny thing was that I managed to write it in a couple of hours since I had a clear mind after some good tea). I had once been thinking of writing a book by collating old materials, data, interviews with various tea masters to lay down in concrete some write ups that are worthy of passing on to the future generations of tea lovers to come, but this would mean another few years of writing and subsequent challenges with finding publishers and getting it on the market etc, and as such, perhaps I might just simply give a rough summary/preview on the issue of Yixing pots and its role in tea. This write up would not have been possible without the kind guidances of many tea masters, many excellent books that were cross referenced, re-rationalized and reinterpreted, and hours, days, months of constant experimentation all the time to validate some of these findings to present them in a rational scientific manner.

This write up is generally about what Yixing clay pots does to tea, from the tea perspective. This is to be distinguished from the other dimension where Yixing clay is appreciated, the artistry of the workmanships of masters, carvings, vessels of refined shapes, beautiful colors, lovely textures.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Tea mastery, is all about being able to create a brew of tea that one enjoys and remembers. A local tea master gave a good example on what this means. If you go for tea with him or with anyone else, and at the end of the session, for the next few days, months, crave for that delicious brew, that is a good brew of a good tea.

Tea mastery, and good tea, is not about telling people to accept and appreciate a cup of tea as what it is. Much as the wabi-sabi concept from the Japanese is a beautiful concept on its own, it can be exploited by merchants and others in the trade as a cover up for lack luster or low quality tea. Our lives are filled with materialisms and its pursuits, we love fine clothes, we like great wines, we desire delicious foods, and similarly, would always go for fantastic tasting teas as well.

Do not feel the pressure from the merchants, the “tea masters” or so they claim, on how the tea is like, how good the tea or brew is. You are the one tasting and drinking the tea, if the flavor, brew, taste, does not agree with you, then such a tea is not worth your money! It is like me becoming a durian seller and telling you how creamy, fragrant, salivating this Mao Shan Wang cultivar of durian from Pahang, Malaysia is like, and requesting you to eat it, and appreciate it from my guided perspective on durian. Many western palates would freak out at the thought of this, although they haven’t really learnt to freak out at the thought of bad tea.

The same goes for tea wares, and the issue of people having only mildly translated, and often miscommunicated informations that end up propagating like wild fire through out the internet and all the various little merchants that pop up like little mushrooms in a field. There’s often talk on certain material type is the best for all tea, and that the royals in Qing dynasty used it, the royalty in Qing dynasty loved their gongfu tea processes, their pu-erhs and all that. Hogwash! There are people replicating qing tea pots in the recent decades, and to justify every batch that suddenly surface on the market, stories have to be spun. It is necessary to be mindful and not fall for some of these fanciful stories. Gongfu tea remains a very southern style of brewing, it almost never crept north. Bulk of Qing “official/royalty” 官窑 tea wares are larger porcelain pots and gaiwans.

You can visit any tea competition, tea grading etc, all they use is white glazed ceramic wares, no one uses yixing pots in the brewing of teas for grading and competition. This would mean that white glazed wares are sufficiently good enough for people to evaluate and enjoy teas. What is the first vessel that anyone should buy when he/she is new to the tea hobby? A gaiwan, preferably white glazed, right size for easy handing and the correct properties (to be covered in another article in some time distant…). I’m not attempting to discount what yixing pots can do to tea (if you finally understand the principle of why they work), but if the tea needs to be brewed in a yixing pot to be tasty, and that it tastes bad in a gaiwan, then something is queer with that tea. Sometimes using a yixing pot can be detrimental to some teas as well.

Yixing Tea pot Clay type

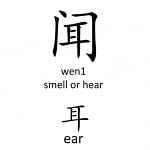

– There’s big buzz about clay types all the time and all the amazing things it can do to tea. Actually what is pure clay? Yixing clay is just a natural occurring blend of chemical compounds, silicon dioxide (when fired at very high temperatures can become glass), iron oxides, calcium oxides, aluminum oxides at different ratios. Just having less of iron 3 oxide and more of iron 2 oxide can drastically change the color from dark purple to reddish purple. Mining in a strata, you would expect gradients as clays transition from one type to another. If you see the picture on the top of this page, how many clay types can you identify in the picture?

– The more relevant way to describe clays would be how “classical” or how similar it is to certain clays of certain eras.

– But I shall not cover the clay type in this article, and the effect on tea, in an earlier article I had explained the surface catalysis properties of different clay types

– A new concept from Japanese sources seem to suggest that the clay works by leaching minerals and metal ions into water to change the taste of it. It is a strange new concept, although very slightly plausible, the ability of well fired pots to leach would be quite limited. Mineral water contains a couple hundred milligrams of minerals per litre. Would it mean a teapot of 100 gram weight, if immersed in 500 litres of water, would dissolve and disappear? The rate of dissolving is so slow, so it would be unlikely to happen in a life time

– If you keep your pot dirty on the inside, the surface will end up being blocked and will be less catalytically active over time, and will also be unable to leach minerals/ions.

Yixing Heat Loss Coefficients

The first secret to yixing pot is the heat loss coefficient. No one talks about this, but it is a very simple concept. Just to guide you through, imagine this :

1) A cup of hot water off the boil, is 100 degrees Celsius, will start to cool to room temperature over time

2) The greater the temperature difference from environmental temperature, the faster the water will cool. If the surrounding temperature is incredibly hot at 90 degrees Celsius (which is impossible but just used here as an example), the boiled water will take its own time to slowly cool down.If the surrounding temperature is very cold like below 0 degrees Celsius, the boiled water will cool very much faster.

3) When you add boiling water directly into your yixing pot, wash your tea leaves, and re add hot water, do expect that the water in the kettle on a stove, at 100 degrees Celsius, when it leaves the spout the water will be probably 96-98 degrees, and once it hits the yixing pot it will start cooling from there, cooling rather quickly in the beginning first ten seconds or so and slowing down over time. The same for water into a gaiwan.

4) Some clays types and some pots with thick walls result in even faster heat loss.

5) The smaller the pot the faster it cools, imagine a tiny drop of boiling water versus a huge bowl of boiling water, the tiny drop will cool faster, the huge bowl slow. So big yixing pot, big volumes of 200ml, 300ml, 500ml, will cool far slower than a small pot of 40ml, 60ml etc.

6) Prolonged Extreme hot is bad for tea most of the time, with the only exception on old teas where the “qi” is weak, and the tea starts to fade and you need extreme hot and even boiling to get the flavours and aroma out. To test it yourself how bad extreme hot can be, just take a thermos flask, pre warm the interior, add in boiling water again and your favourite tea, close the cap and leave it for some time before dispensing the brew. You will get a “vegetable” soup instead of tea.

7) A brief moment of extreme hot is often necessary to “waken” the tea, push out the aromatics, help unfurl rolled teas etc, but sustained extreme hot can spoil the brew, causing over extraction of astringent compounds. If your water is not hot enough, your rolled tea leaves will not unfold enough to allow proper brewing.

8) As such, different yixing pots, clay types, firing levels, shapes, wall thicknesses, have different thermal loss coefficients that determine how long this “extreme hot” phase is (usually matter of seconds), and subsequently how “cool” the tea is being brewed for in the next minute or so. That will determine the brew output, on how aromatic, balanced it would be.

9) This is also a reason why most gongfu tea is limited to pots that are small, and not incredibly huge at the few hundred milliliter levels. Apart from the tea leaf cost (although sometimes not that prohibitive), the large volume pot is much “hotter” and cools slower, so it is easy to make mistakes in the brewing, causing bitter astringent compounds to be extracted. There is also another reason later to be explained.

10) Clay color can matter, different colors lose heat at different rates, darker colors tend to cool a lot faster than lighter colors. But this is a little challenging to generalize at the moment as different colors in yixing clay is due to different chemical compositions, and as such, by material alone have different thermal coefficients and heat capacities, but just for comparison sake, a Nei Zhi Wai Hong (purple clay pot coated with thin layer of red clay on the outside) may have different cooling rates to a similar pure uncoated purple clay tea pot.

11) So how do you choose a pot to match a tea? Choose one that has a slight sustained “extreme hot” phase to rolled teas. Mid heavy oxidized rolled oolongs can take a bit more heat than green, light rolled oolongs that may end up being vegetable soup like if too hot. Choose a pot with sustained extreme hot, for aged teas. Select one with quick cool characteristics for young, green raw pu-erh teas. Pick one with preferably thin walls for gongfu yancha/dancong etc. If you explore brewing different teas in different vessels over time, you will understand the optimal conditions and optimal brewing durations over time.

12) Another caveat, do not ignore tea quality as well. Extremely good tea is very forgiving, the aroma is rich, intense, easily coming into the brew without much need of sustained “heat”, and yet does not have that much undesirable astringent notes (there will be another article on this matter in the distant future). Average quality teas need to be “pushed” for the aroma to come out, the body to develop, and always runs into the risk of bitter astringencies coming into the brew too. Taste more, buy less, sample more, experiment more and you can start to understand tea better.

13) Steeping Durations is something that is closely linked to the thermal loss coefficients. Its not uncommon to see books, websites, and literature, merchants, telling you to steep in a very “routine” standardized timing, 15 seconds, 30 seconds next, etc in 15 second increments. That is a little too robotic and not “organic” nor flexible. In reality maybe the brew would taste really good if you steeped it for 22 seconds than 15.. and for some teas perhaps 5 second to ten second steeps could be good with increments of a few seconds per steep.

Learn to relax with the steeping duration! If you understand the pot, the tea, then this should be the thought process. The thought process will be different from convention, usually people add hot water and wait for the specified duration. But now, remind yourself when brewing when the hot water goes in, how much of the aroma you want to push out and secure with the brief phase of extreme hot, and then when to dispense is dependent on how you want the body to develop. Tea mastery is achieved when one can control the process and calibrate based on the taste

14) Leaving the lid off the teapot or gaiwan off, to do it or not? After dispensing the brew, the vessel does retain heat and may continue to “steam” the tea leaves if its too hot. If you are brewing a delicate tea, a greeny oolong, or sheng-pu-erh, this steaming will cause the bitter/astringent to come out faster, and potentially the leaves becoming “cooked and vegetal” in taste. In such cases, leaving the lid off is helpful. If you are brewing a tightly rolled, mid oxidation or high oxidation oolong, allowing it to steam in the early durations of brewing can aid aroma and leaf unfurling. If your vessel is huge, which would mean it will retain more heat, then leaving the lid off may be helpful as well. If the vessel is small, 40-50ml, it cools fast, and you would worry less. Such fast cooling of small pots may mean less chance for rolled leaf teas to get unfurled, so for TKY and some Rolled teas, choosing a pot with slightly higher volume, less thermal loss coefficients can be helpful.

15) Having too many pots can be distracting. If you do not run experiments regularly like I do, then limit yourself to a select few pots, repeatedly brewing tea in them to understand the characteristics of the pot and become a master with it. There is a small group of pots that I use daily, with the rest just for comparison or just for “keepsake” whenever I chance upon them at reasonable prices.

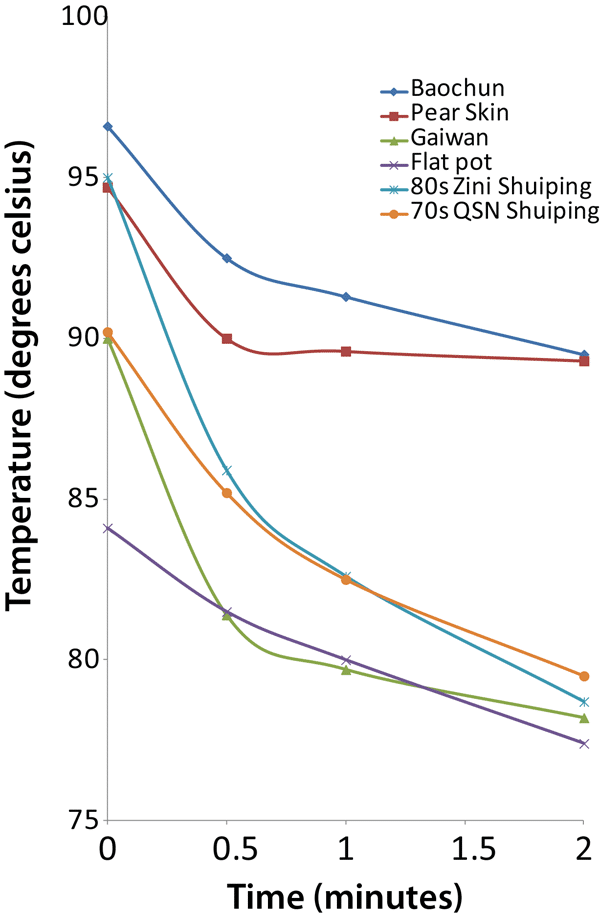

Case Study – Just an example on heat loss of different pots, look at the following measurements with an infrared thermometer over time with preheated pot + boiling water straight into it

Both the Baochun and Pear skin pots retain heat very well, and should be better used for higher oxidation, rolled teas, or aged teas, and should not be used for greenish lower oxidation, nor young green sheng pu-erh. If used for green sheng pu-er, the brewing needs to be really fast to prevent the bitterness from coming out quickly due to the heat.

The gaiwan used here is the “goat fat glaze” style of gaiwan, that is a little thicker, and as you can see, it gets reasonably hot in the beginning but quickly cools to 80 plus degrees in half a minute. So, for some teas, you might want to brew it slightly longer.

The flat pot with thick walls moderates the heat very well and thus can be used for young, green raw pu-erh, it gives more brewing leeway and prevents the quick release of astringent compounds, and also prevents the “cooking” of tender green leaves.

Yixing Pot Shape

This is something that some people do talk about. It is correlated to the amount of space the tea leaves need to unfurl. But there are 2 things you need to take note here

1) The space needed to unfurl is important, compressing rolled teas like TKY into a flat pot will result in an imbalanced brew, the leaves cannot unfurl enough allow the flavours to come out. A round or tall pot can be useful, or a shuiping if you know the right pot rolling techniques (a real gongfu tea master knows this method very well, ask him/her for a demonstration if you know one!)

2) However the shape results in another problem with cooling. Imagine hot water in a tall cup, versus hot water poured into a flat saucer, you will find that a flat saucer will have the water cool faster than the taller cup. This will affect the brew as described previously.

3) As such, imagine for raw green pu-erhs, a thicker wall, flat pot, with right pouring techniques with a kettle on a boil would be able to enable one to minimize the strong bitter, and yet have the aromatics and the body. (tip here, tea leaves can be rather sensitive to scorching by boiling water as plant material, like wood, is not as good a conductor of heat as compared to clay or metals/metal oxides, so if you were to pour boiling water into pots, you might be want to be careful if the tea is green and less oxidized, going around the rim of the pot is important. This is also important in gongfu tea, especially that of Chaozhou brew, where you wouldn’t want to disrupt the tea “gall” or cha-dan that you create in the middle of the pot. Ask your tea master to demonstrate this if you are unclear on how this can be achieved.

Case Study – Why do all these pots brew rather similarly?

All are zini pots made of materials from the 80s type

Pot 1 – 120ml, medium wall thickness, high fired

Pot 2 – 80ml, medium thin wall thickness, high fired

Pot 3 – 100ml, thicker wall, mid high fired

Pot 4 – 60ml, thin wall, quite high fired (not excessive).

When brewing the same pu-erh sheng tea that is just a few years old, brewing at a ratio of 1 gram per 20ml, Pot 3 performed the best, whilst the other 3 pots perform rather similarly.

Analysis :

Pot 1 – Higher volume, so retains more heat, but since wall is medium thick, it compensates a little and cause some heat loss. Fatter and taller than the rest, so slightly better heat retension.

Pot 2 – Lower volume, so less heat retained, but wall is thin, so less heat loss to the material, flatter pot, loses heat fast

Pot 3 – Reference for comparison against the rest, thick walls, with boiling water into it, allows the tea leaves to quickly push out the aroma before the body slowly develops. Flattest and as such cools faster than other pots, may be useful in prevent bitter notes or vegetable green notes from accidental tea leaf cooking

Pot 4 – Small volume, less heat retained, but much thinner wall, so helps conserve some heat. Rather high firing, so does not rob aroma.

Yixing Pot Elution rate

It’s a fancy term for how fast the pot pours.

1) For small pots, elution can be fast, in matter of a few seconds for some pots. The larger the pot volume, the slower the elution, and this will run into the risk of over-brewing, and if the water is too hot, this slow down will also end up with some scorching. Large pots can take up to tens of seconds to pour, so your aim of steeping for 15 seconds or 30 seconds is actually very much longer.

2) In gongfu tea brewing, the rate of pour needs to be considered to avoid under or over brewing the tea. In proper chaozhou gongfu tea, you might want to be able to elute the tea as fast as possible, five seconds to eight seconds if possible as any additional split seconds will end up with strong bitter/astrigent being extracted. you may choose to discard this portion of the brew if you didnt manage to catch the timing. This will perhaps be explained in a gongfu tea article in the distant future.

3) Certain pots are designed to elute really fast, i.e. flat xishi style, this can be useful for chaozhou gongfu brewing

4) Some pots elute in beautiful thin streams, the height of eluting, the bubbles it generates when the brew hits the pitcher can be useful in “oxidizing” the brew and cooling the brew, so that it will be just right for drinking, and the oxidation, in smoothening out the tea.

5) Choose the right pour rate for the right tea, and calibrate based on your brewing expertise.

Yixing Firing

If you had read the previous article on the catalytic properties of yixing clay, the firing matters.

1) Under fired pots, or low fired pots are extremely porous, they absorb aromas, catalyze the oxidation of high aromatic molecules, robbing the fragrance. A pot made of rare clay but not properly fired, would not perform well for tea.

2) On the other hand low fired pots can help smoothen out the roughness of teas, the bitter edges etc

3) As a rule of thumb, go for at least a mid-high fired pot, and you may wish to avoid the very high fired ones. Over fired yixing pots are “glass” like, almost like porcelain, glass, so why spend money on such yixing? You can easily buy a glass or porcelain glazed pot for cheap..

4) To tell the firing, one usually uses relative comparison amongst other pots in the same batch, although its been said that with adequate experience one can quickly tell. Just by rotating the lid on the pot and hear the abrasive ring, it can be an indication of the firing. If it is dull, porous, it could be under fired. If it is metallic, reminiscent of a bell, it could be well fired, on the high side.

5) Low fired pots take a really really long time to shine, and sometimes they don’t really shine at all till many years of usage

6) Well fired pots or rather perfectly fired pots would start to show happy signs of glow with just a few uses.

7) Depending on how well hammered/compacted the clay is, sometimes some clays can be rather metallic sounding despite being less highly fired than others, this is due to over hammering/compacting of the clay material when making tea pots.

Perhaps some of you might find this information new, but it isn’t new, it is all the knowledge and wisdom of generations of tea masters condensed. Unfortunately, not much of these concepts, ideas have made it to the west, and not even in china. I’m not a tea master, but simply a conveyor and consolidator of informations. If you come across people claiming to be tea masters, question them, test them, if they meet the mark, then learn from them, if not, the risk of being led astray is there.

With your existing pots, start to understand the nature of each of them, and suddenly it becomes extremely clear what tea to put into which pot, together with brewing durations and brewing techniques, one can verify whether they had been able to achieve a more delicious brew with an yixing pot versus a simple gaiwan.

There’s a lot more to tea and tea ware that can be investigated by science, for example if you have pure hong-ni tea pots, when you add hot water to it, the color does deepen by a little bit. And after more usage, the color remains permanently deep. The current speculation is probably due to red shift caused by thermal expansion. Till then, I will need to find more time and inspiration to write 🙂