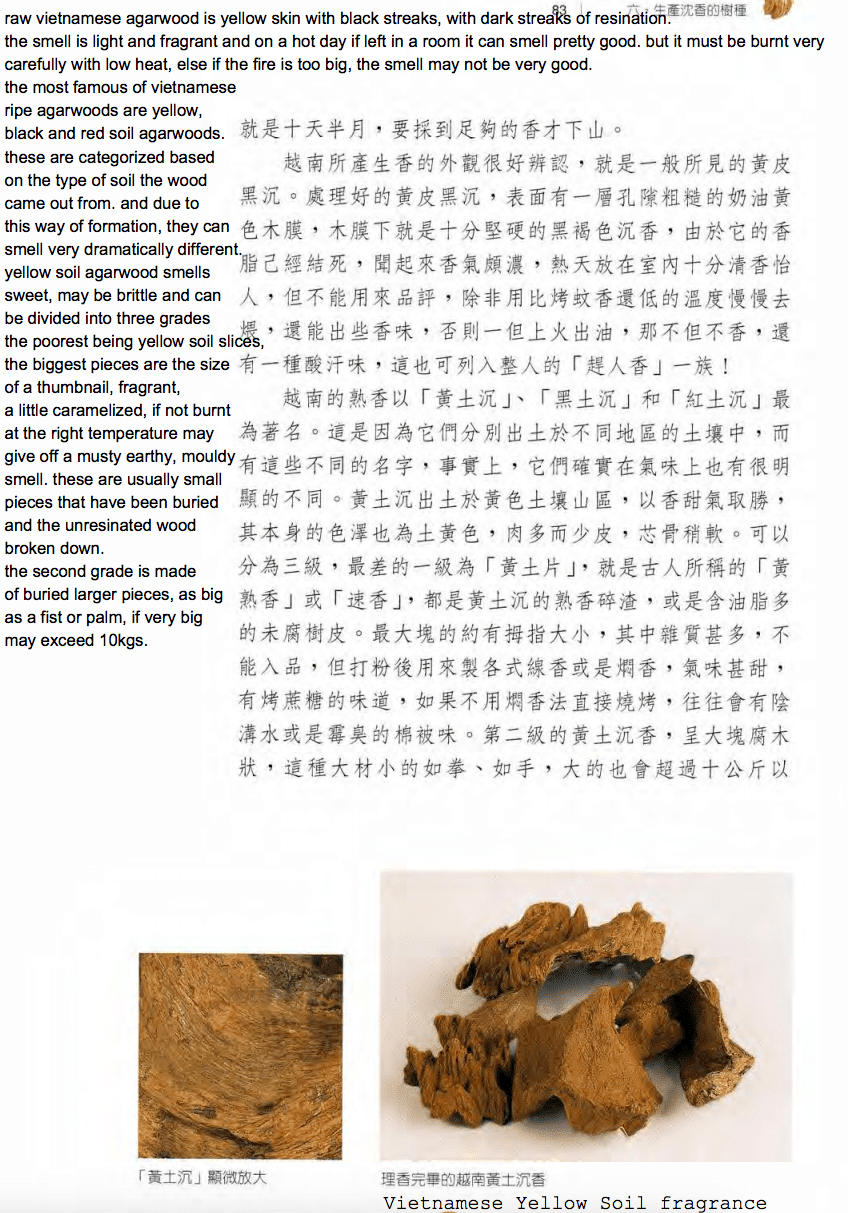

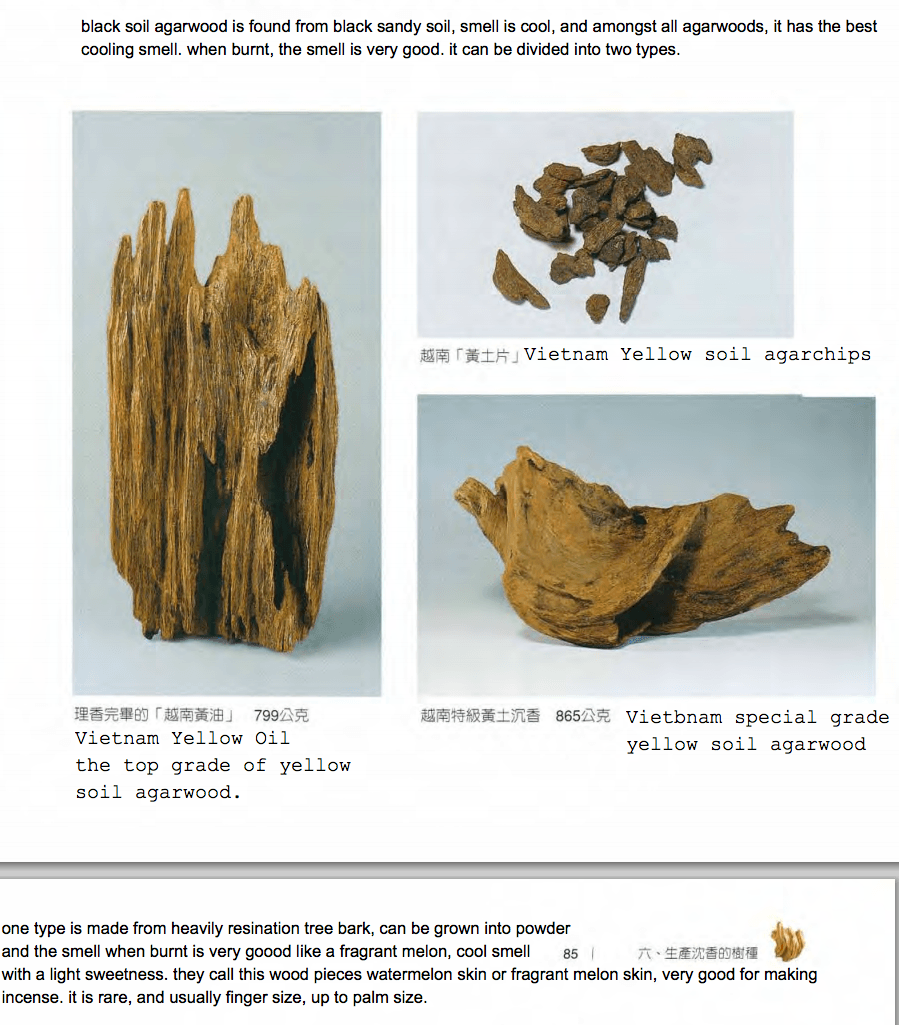

There are two obvious lines of soil agarwood on the market, one from vietnam, and the other from Indonesia. The Vietnamese line consists of 3 types of soil agarwoods, yellow, red and black soil.

In Indonesia, some call it yellow soil, but it is just Irian/Merauke’s Filaria material, and occasionally some papuan. But that said, the Indonesian filaria material is so simple to distinguish, because of the strong herbal note when burnt or strongly heated. It is easily ground into fine powder, and has made its way into adulterating all sorts of agarwood incenses from different origins due to its low cost. The lowest grades used to go for tens of dollars per kilogram..

In the 80s, Prof Liu Liang You, one of the top incense culture masters in Taiwan had written that soil agarwood is equated to “Ripe agarwood” since it has seen many years of erosion and weathering. This coincides with the ancient/traditional chinese classification of “黄熟香” or yellow ripe fragrance, or in japanese, Otjukukoh. There are 3 colors to vietnamese soil agarwood, yellow, red and black.

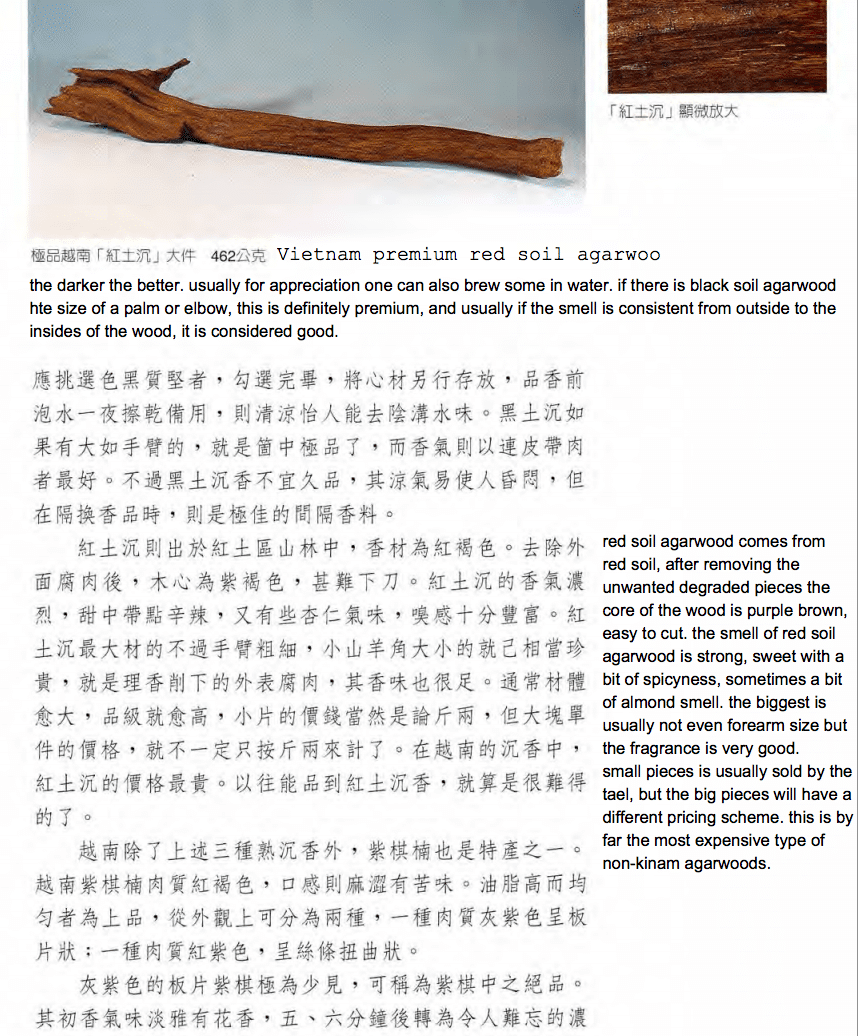

Below are the images of Prof Liu’s book that i had translated the relevant parts into english a couple of years ago.

The whole of Taiwan right now still lives by Prof Liu’s legacy and classifications. Soil agarwood is distinct and distinguished from kynam in the Taiwanese context. Even in one of the biggest chinese/taiwanese ventures, i.e. F*sh*n K***, in their woodchip sampler set, Qi-Nan is made distinct from Red Soil, with the real Green Qinan at a price of about a thousand dollars a gram. On the other hand, the same company is breeding another “monster”, they have an incense series that are named like 6 “points” Qinan, 10 “points qinan”, Gold Qinan and White gold Qi-nan, some of which uses the cheapest of kalimantan and irian materials. Why do they want to do that? Because this naming strategy and marketing scheme is one of the routes to making them lots of profits. If you ask them upfront, they will tell you these products do not contain real Qi-nan, but just a mimic of the olfactory profile, something along the line of a Qi-nan inspired product.

*disclaimer : At this point of time I would like to make it clear that I have no interest in engaging any of these people whom are doing these things, whether scrupulous or unscrupulous. It is a free market, everyone has their own faiths, own school of thoughts. Everyone wants to make money/profits, some do it through upright and honest means, others do so by duping or misleading. Whether their actions are right or wrong, it is not for me to judge, but the consumer, as long as eventually the consumer is satisfied even when having to be a “sucker for punishment”.

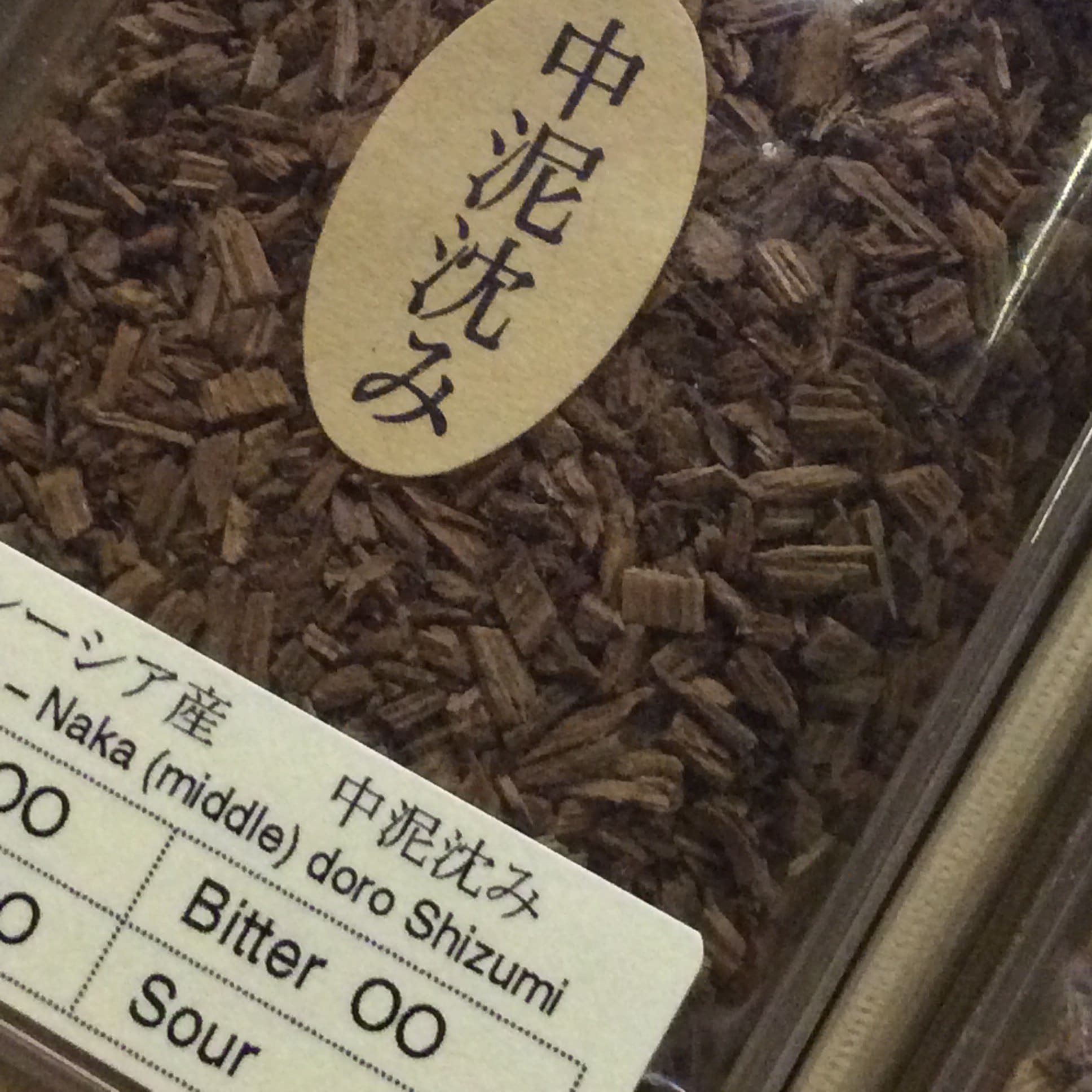

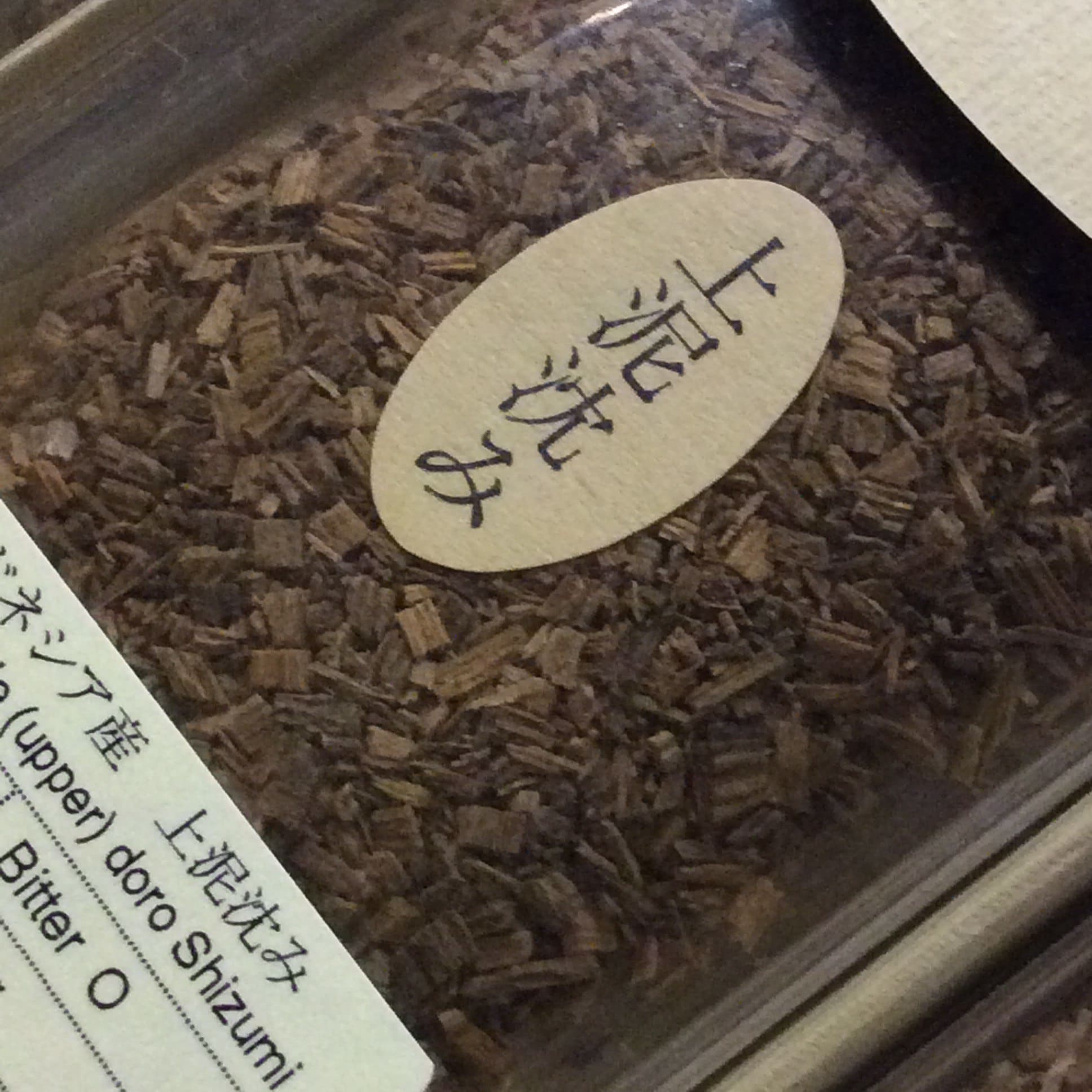

In Japan, soil agarwoods fall under the “Jinkoh” umbrella, with some big suppliers, i.e. Nisaburoshoten, creating a category called “泥沈香”. Others would just consider it a different grade of Jinkoh, i.e. 沈梗. This was never fused into the “kyara/kynam” category.

Ue and Naka grade “Soil” agarwood in Japan.

Ue and Naka grade “Soil” agarwood in Japan.

Kohgen’s Jinkai, excellent incense with the melon skin note, made from 沉梗 or soil agarwood.

Abit pricey though, 50,000 yen, for 50 grams of incense, but extremely lovely. With this stick, you can easily compare the difference between a kyara stick and a soil agarwood stick.

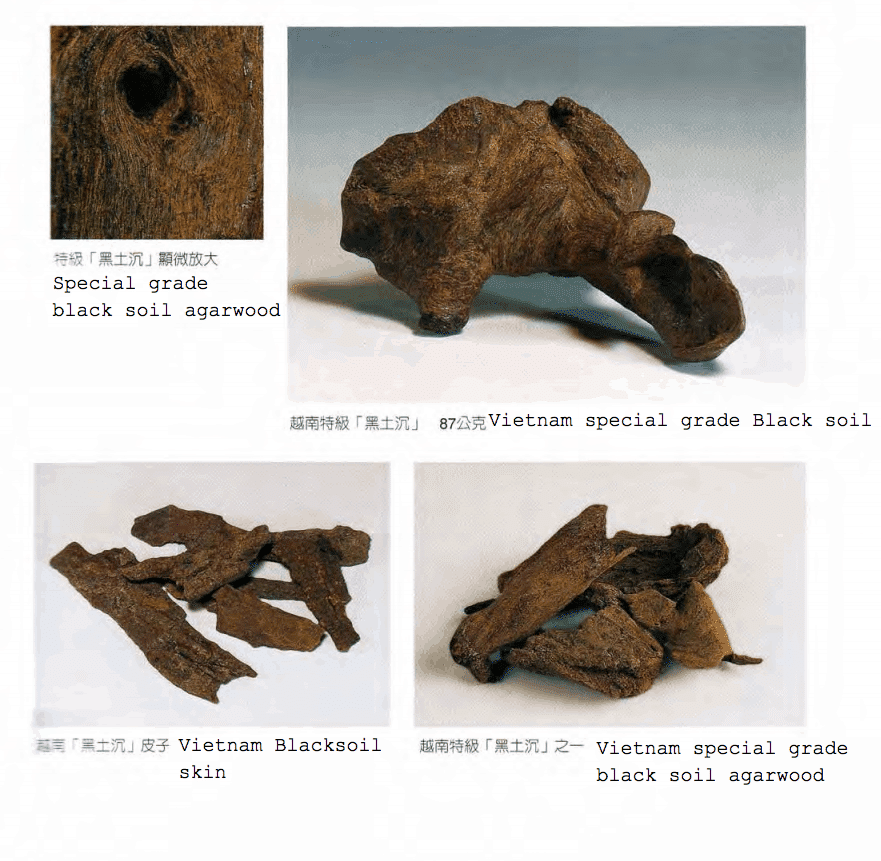

New Generation Red Soil material seen in vietnam, April 2015. prices range from 10-30/gram.

How close is this to the original/traditional red soil and how does one tell the difference? hehe! Why did “new generation” soil agarwoods appear on the market in the past few years? This was because of shortage of real soil agarwoods from Fu Sen region, and some people would bury lower grade fresh harvested Nhatrangs in soil so that they can sell the same material for several fold more later on after making it look like soil agarwood.

How does one “qualify” soil agarwood as a collector or hobbyist?

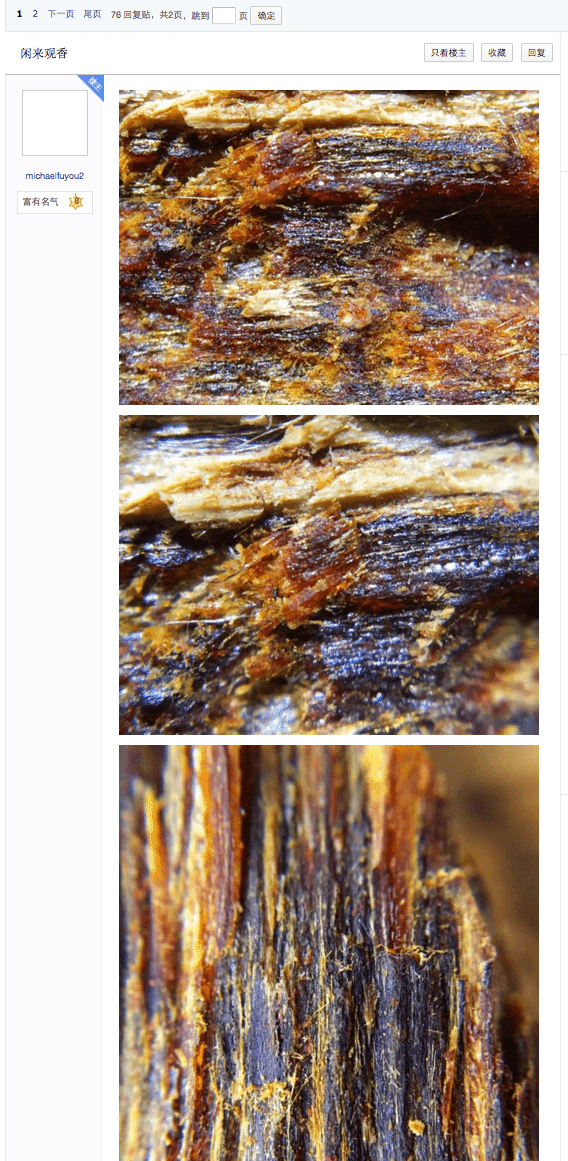

Here are some photos of the proper soil materials from the olden days, images courtesy of 心香一炷胜沉檀, China

Having been naturally buried for decades, centuries, most of the fibres of the material would have disintegrated already, the soil agarwood will feel hard and brittle, and the remnant of the fibres on the outside of the agarwood gives it a distinct color for classification. Seriously, the division of yellow or red or black soil is simply due to color of the wood influenced by the soil it is buried in!

And if you slice the wood above open, you will see nice compaction and really high resination.

This is what people would refer to as the “Meat” of the wood.

Similarly, the above yellow soil agarwood (premium), when lightly shaved, it reveals the beautiful “meat” within.

Over time of being buried in depths and subjected to lots of soil pressure, erosion, weathering etc, the material can also form cracks on the external surface, but the overall “meat” inside is excellent resination.

If the material is very spongy and fibrous inside and outside, it runs into the chance of being recently buried, since the signs of age and weathering is not present at all. If the resination is thin, that would also raise some questions as well.

Many years ago, the Chinese entered the agarwood being unaware, unknowing, buying up almost any agarwood they could lay their hands on as they had been preached to that agarwood is rare, hard to obtain etc. But in 2015, if you meet the mainland chinese whom are dealing with agarwood, and those whom are scouting the Singapore markets, they have learnt so much and so quickly, they are still willing to pay good money, but only for very selected amount of materials that meet their criteria. The wise ones, learn very quickly.

On the major chinese forums, the mainland chinese can now discuss to the level of distinguishing kynam from “qi-rou” and “soil agarwood”, and that they are not the same thing! And that is only from a couple of years of agarwood boom in china, a sign of how fast they are wise-ing up.

Chinese collectors are now extremely knowledgeable even discuss to the extent that if one scrape a piece of soil agarwood, the powder obtained is crumbly, powdery to touch. If one scrapes a piece of kynam or kyara, the powder obtained is sticky and clumpy.

Does the Chinese now know Kynam proper? you will be surprised that they might even known more than what the West knows, that is because they had shelled out top dollar, be it $1000 per gram, $2000 per gram, that in a short period of time, they vacumned a lot of material from Japan, Hongkong, Taiwan, Vietnam, both real and fake, and studied them intensely. You can check with all the major japanese incense houses how much business they receive from China now, oh god, a fraction of a billion chinese people in China are all abuzz about kyukyodo and kurobou nerikoh, and another fraction crazy about japanese incenses.. yet another bunch on agarwood.. etc Japan, Hongkong, Taiwan, and Vietnam are just scrambling all they can to feed the monster. Every big and small incense house in Japan offer agarwood/kyara authentication and valuation, at NO cost, because they have run out of supply and need all ways and means to obtain some. Feel free to get the appraisals from a few of them just to see if you can get the best price for your material, if it is good.

Here’s an example of the kynam that the chinese are playing with, on one of their public kynam forums, not a very big one, probably about 4000 members and 70,000 posts. That pales in comparison to their agarwood forums, which is about 110,000 members and 1.6 million posts.

Whilst I’m impressed to see the maturation of agarwood appreciation in Mainland, being somewhat Chinese myself, it is always common that the mainland Chinese bore the brunt of the blame when it came to agarwood extinction. But having studied and observed the Chinese market, I don’t think the Chinese should be blamed. Why did old growth wild agarwood go seemingly extinct in assam, cambodia etc? When that occurred, the Chinese were not into agarwood at all! The Chinese did spend the past few years buying up a lot of sinking agarwood materials. Since sinking agarwood has too much resin, it was not viable to be made into incense sticks, some of the sinking materials made it into monkoh style woods where tiny amounts are appreciated. Most of others became pendants, beads, bracelets, and all sorts of decorative paraphernalia. Not so much was “consumed” and burnt into nothingness, instead, they were preserved and appreciated in various ways.