I was inspired to write this article when I had the fortune of viewing, and handling a 供春 “Gong Chun” Yixing pot made by Jiang An Qing (1920s). No pictures though, in respect of the owner’s preferences. Amongst the opinions of high end Yixing collectors in the world, no one could make a Gong Chun pot better than Jiang An Qing, not even Wang Yin Chun, Gu Jing Zhou etc.

Gong Chun Pot from Artxun

It is rather baffling, since there are so many famous makers, artisans and masters over the centuries, what was so difficult with such a pot design and its significance?

We have to re-visit the story of Gong Chun and how the Gong Chun Pot came about.

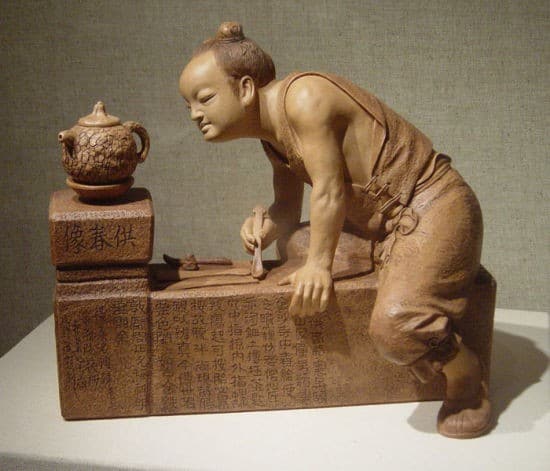

Xu Xiu Tang’s Gong Chun Figure

Gong Chun (1506?-1566?) was a servant to a famous Ming Dynasty Scholar, Wu Yi Shan. They had gone to Jin Sha Temple in Jiangsu, Yixing, when Gong Chun had the chance to observe a monk making teapots/wares. Gong chun mimicked what the monk had made and learnt from the monk some of the teapot making tips and methods. By his own interpretations, experiences and based on what he had learnt, he made the “legendary” Gong Chun pot, which was never superceded by clones.

If you look at the museum copy of the Gong Chun pot supposedly made by Gong Chun, or the item made by Jiang An Qing, if you do away with the lid, its spout and handle, cut the top off a little.. and suddenly you have in your hands a Raku bowl of some sort!

The Gong Chun pot had a crackled surface that was a result of the clay material shrinking when Gong Chun had left it in the sun to dry. It was a bit out of shape here and there, with natural looking deformities on the whole pot body, the handle, spout etc, evidence that it was a hand kneaded and made pot without the use of molds. In its natural beauty, you might realize that the maker had never intended the pot to look like a tree stump nor a tree burl, he was just trying to make a pot!

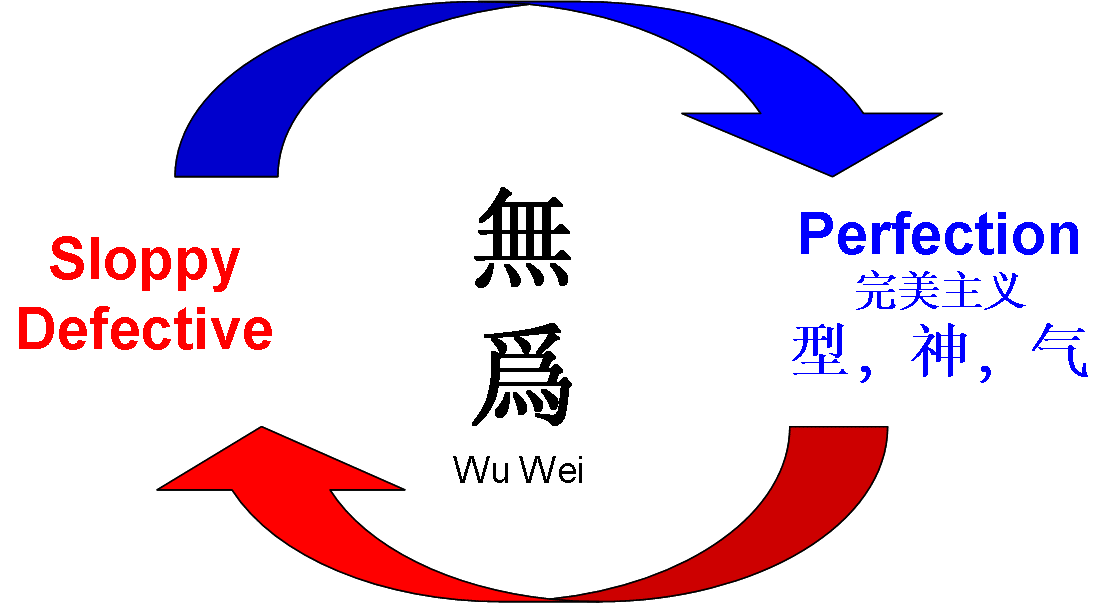

The Gong Chun pot is one of the very very few yixing pots that stems from the notion of Wu Wei.

99.999999999999% of all other Yixing pots through out the centuries, and even till now, focuses on the pursuit of perfection, on how well it mimics natural elements, plants, animals, perfect geometric shapes and much more. Masters like Wang Yin Chun, Gu Jin Zhou, Shao Da Hen, and many more through out the centuries are known to be at the top, nearing or at “perfection” of Shape, Spirit, Qi, firing etc.

Wu Wei, if you google, brings up a lot of “taoism” related content. Actually wu wei is not something that is confined to a religion. Religion and classification are boundaries set by the hand of man. Wu Wei is something along the line of non action, but not being passive, not causing nor not uncausing. It is not subjected to cause nor conditions, non dependent in origination, and is perceived to be natural.

This is central to what the Japanese consider to be the Wabi Sabi aesthetic. In Zen, an object possesses the wabi sabi aesthetic, if it is able to inspire the sense of wabi sabi or that the viewer could observe the wu-wei in the object.

As for Gong Chun, at the Jin Sha Monastery, which is a Zen monastery in the Ming Dynasty, he must have had been influenced by Zen philosophies, and similarly, the Jin Sha monk would also be making pots/tea ware based on such an attitude/perspective, which is no surprise why the Gong Chun pot looked like that.

Wabi-sabi is subject to conditions and it is not bound by its current physical form.

Why is that so? Because imagine the fact that you have had a chipped tea bowl that inspires wabi-sabi in you every time you see or handle it. If the object is sent to an expert replicator without you knowing, with modern technology, and exactly duplicated, if you see the either object separately at any one time, you will still perceive “wabi-sabi”. But if you come to know that it has been duplicated, and when the two objects, or many more copies are put together side by side, suddenly the “wabi-sabi”ness dwindles, despite identical physical forms.

Wabi Sabi Does not exist in the material of the object.

Take for example a Shigaraki rough pot from Tachi Masaki. The pot, with its crude roughness, individuality, may inspire some “wabi sabi” in some, but that is achieved not because of the material. The material argument falls apart when the pot is crushed into a fine powder, or if one visits the mine to see a mountain load of the clay lying on the ground, where has the “wabi-sabi” gone?

Existence of Wabi Sabi is interpellatory

Its existence depends on our existence. If the perceiver does not exist, does “wabi-sabi” exist? So in the end Wabi-sabi appears to be a combination of contributions from various aspects that acts on our consciousness. It is something that arises in one’s perception/consciousness. It is more qualititative than quantitative

Wabi-Sabi exists through contrasting difference

Wabi Sabi has a tendency to be invoked when an object differs itself from all other existing objects.

If you have 4 tea cups that came from the exact mold, the patterns on it are identically printed, but when fired they warp into different shapes, when viewed as a group, the cups appear to be able to inspire some “wabi sabi”.

Similarly, if the cups are hand painted, and each cup has differences from each other, there is some “wabi-sabi” invoked too.

This would also mean that objects that are unique, one of its kind, have a higher chance to inspire “wabi-sabi”, i.e. tea bowls of bizen, raku, and many more.

Pleasure of the Senses

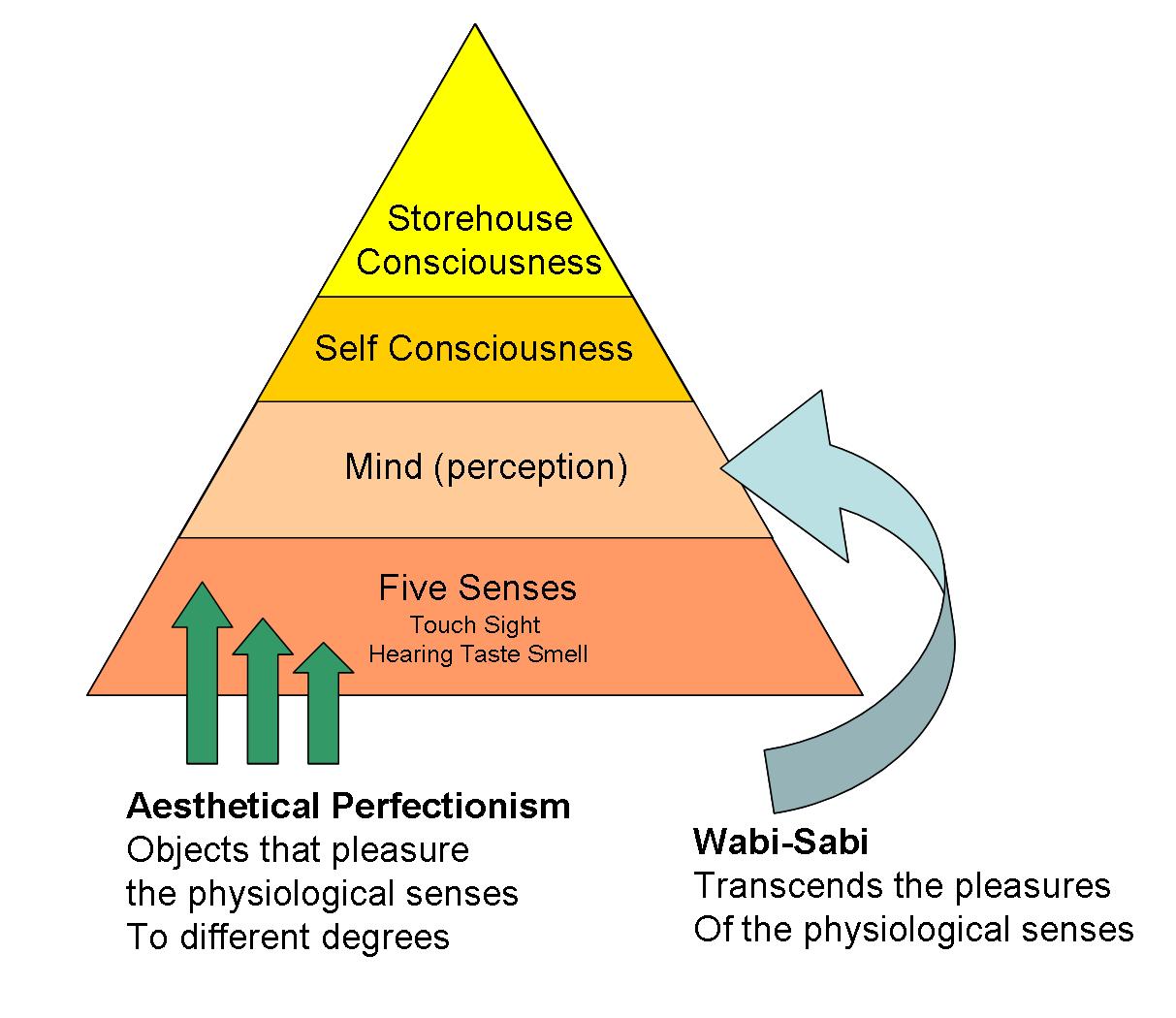

There are multiple levels of consciousness as described in buddhism. Objects of aesthetical perfectionism, induces sensory pleasure to the physiological senses at several degrees. Through the foundation of aesthetical appreciation the five senses, the sixth consciousness, i.e. mind perception and cognition is then invoked. Wabi-sabi appears to bypass the foundational five senses and exert its effect directly at a higher mind level.

A Wabi Sabi Object is non-slip shod nor pretentious, not careless nor exaggerated, not shoddily flawed nor perfect. It inspires the viewer to live in the present moment, and become aware of the transience of things in a “wu-wei” manner, a tetralemma of neither being the extremes nor not being the extremes.

What goes on in the mind of the creater/artisan when such an item is made?

the maker is in a state of “wu-wei”, in the present moment, going with the flow of time. This 意 “intention” or the lack of, is embodied and absorbed by the product. The drive is not to create a perfect object, nor a flawed object, but just creating “an object” without expectations.

Union and responsiveness is essential (*update, a very valid and important input from a friend)

As the potter makes an object, the potter is not the only one shaping the clay, but the clay is also guiding the potter in the process. There is a communion between man and nature, where man does not impose his own will on a natural element, instead, listening to the material and working with it. He allows his creative ideas interact with the material in a way which sensitively acknowledges the material’s essence and shapes its life in a dance where they are equal partners. It is a responsiveness in which man is guided by a natural force that resides in the essence of the as yet unmade object, and the object allowing itself to bend to the energy of the creator.

In contrast, when a master yixing potter is creating a master piece, the processes that go on in the mind is different.

Perfectionism. How the spout should be shaped, how the lid should fit, how the body should be geometrically correct, good proportions, thickness, the clay pounding, the quality of the joints, the surface condition, the clay quality. There is almost some obsessive compulsiveness in the process. These potters know and control the exact kiln conditions, correct surface treatment that when the pots are fired, the outcome is as what they expect and prefer. This is unlike in “wabi-sabi” related wares where the potter does not have any control, does not have any expectations nor preferences on the outcome. It is what it is.

So now, you might start to understand why WYC, GJZ, ZKX and many more, could not well replicate a gong chun pot.

Once you have understood a little of wabi-sabi and the wu-wei approach to art and tea, then suddenly it seems not as ideal to pursue crazily expensive teas that are the best of the best in their class, lao pan chang, ping dao and what not. Owning and drinking these teas is just to rub the ego. It is the human mind that is the biggest obstacle.